Executive Summary

The Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) is one of New York City’s most essential engines for opportunity, equity, and community vibrancy. By investing in after-school and summer programs, leadership development, career pathways, literacy support, and services for runaway and homeless youth (RHY), DYCD ensures that young New Yorkers have safe spaces, trusted mentors, and real chances to succeed. Beyond youth programs, the agency anchors neighborhoods through adult literacy classes, immigrant services, workforce training, and community hubs like Beacon and Cornerstone centers. DYCD also administers the majority of the City Council’s discretionary contracts–approximately $214 million in Fiscal Year 2026 (FY26)–making it a critical partner in advancing community-based services across all five boroughs.

The work of the agency is guided by eight principles to fulfill its mission: Opportunities for All, Stewardship, Holistic Approaches, Being a Learning Organization, Integrity, Strategic Relationships, Inclusiveness, and Community Voice. While DYCD is committed to following these principles and delivering core services, ongoing challenges–including a consistent lack of funding and resources, minimal program expansion, inadequate communication with providers, and a lack of strategic planning–hinder their progress toward reaching its guiding principles and core goals. The agency remains chronically underfunded, and the resources provided to the agency often fail to align with the critical and time-sensitive needs of providers and programs. This resource gap is further worsened by systemic communication breakdowns between the agency, its contracted providers, and the very communities it is meant to serve, undermining progress towards its mission and goals. Moreover, the agency’s lack of a comprehensive, up-to-date, strategic plan suggests that internal staff and external contractors are not aligned. This results in an inability to accurately evaluate program outcomes and effectively utilize feedback from providers and the community.

Access to shelter, after-school programs, disability accommodations, language services, and job opportunities for young people is essential to making New York City not only a symbol of hope, but also a model of diversity, opportunity, and shared success. DYCD has shown a real commitment to its guiding principles and, despite funding and other obstacles, has built strong partnerships with program providers and continues to passionately advocate for its mission. There is great potential for strengthening the agency’s core work and services with adequate funding, resources, and greater investment in cultivating internal leadership. Now is the time for the City to deepen its commitment to the important work of DYCD and to the programs and services that support the children and youth who call New York City home, and to ensure that they have the foundations they need to thrive and grow.

Note from the Evaluation Team

The evaluation team would like to make it clear to readers at the outset, that while the Department of Youth and Community Development has been graded across six pillars and associated indicators within such pillars, those grades may not reflect actual conditions on the ground. While this report card initiative was launched by Speaker Adrienne Adams on March 13, 2024, the ability for the City Council to engage with senior DYCD leadership and receive information from DYCD was critically handicapped by the Mayoral Administration at every step in the process.

Key information that could better inform the public about the performance of the agency viewed through the report’s pillars has not been procured for the Council.

The evaluation team has graded the Department of Youth and Community Development with the information received. Due to the Administration’s intransigence on cooperation with the Council, this report and the performance evaluation of DYCD is incomplete. Please see Timeline for a more detailed timeline on engagement between DYCD and the Council.

Key Findings

Recommendations prioritize communication, meaningful engagement, comprehensive case management, and long-term strategy planning.

- DYCD would greatly benefit from developing and publicly releasing an agency-specific strategic plan to ensure that the public and providers understand DYCD’s vision.

- DYCD needs consistent and clear funding timelines to ensure that providers are being compensated properly, and communities receive resources when they are most needed.

- DYCD’s collaboration with other governmental bodies and City agencies is greatly hindered by mayoral oversight; the agency should be granted more autonomy over its primary functions.

- More consistent communication and transparency with contracted providers is needed from the agency to ensure that DYCD-funded programs are serving communities as intended.

- DYCD should have a clear plan and vision for how they use provider feedback to improve their internal and external processes.

- DYCD maintains strong recruitment and development efforts but needs a larger share of the budget to increase CBOs’ pay and strengthen agency support.

- DYCD would benefit from improving communication around how the agency’s digital efforts support DYCD’s wider strategic vision and the City’s consolidation efforts through OTI.

- The agency also needs to focus more on simplifying the end user’s digital experience, from providers to communities in need.

- DYCD should reevaluate its program evaluation and performance measurement metrics to have a larger focus on programmatic and participant outcomes, while also setting more ambitious targets that will strengthen service delivery.

Leadership, Strategy and Direction

Service Delivery For New Yorkers

Relationships and Collaboration

Workforce Development

Financial and Resources Development

Digital

Government

Measurement, Analysis and Knowledge Management

Leadership, Strategy, and Direction

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Leadership and Governance | C |

| Strategy Development | D |

| Strategy Implementation | C |

- Leadership and Governance

Agency Strategy

Leadership and governance are important in local government for guiding strategy, policy and programmatic direction, and for ensuring that available resources are being used effectively. Leadership also helps in determining how to set out the nature and scope of an agency’s strategic objectives in enough detail to encourage implementation and to ensure that its chosen strategic direction is being communicated effectively to the public.

DYCD’s mission is to invest “…in a network of community-based organizations and programs to alleviate the effects of poverty and to provide opportunities for New Yorkers and communities to flourish.” Its vision is described as improving “the quality of life of New Yorkers by collaborating with local organizations and investing in the talents and assets of our communities to help them develop, grow, and thrive.”

The agency is primarily responsible for the City’s youth-orientated strategic planning, service coordination, policy development, and related public and community awareness efforts for its relevant services and resources. In pursuing its mission and vision, DYCD principally functions as a partnering agency across multiple service areas. Through formal contracting, strategic partnerships, and collaboration, the agency works with CBOs and other local institutions, schools, and community members, to build capacity within available resources.

As a government agency, DYCD has a responsibility to the public (and the City Council) to identify and explain how it intends to meet its statutory mandates and spend the public money it has been given the authority to spend. DYCD’s leadership decisions, its strategic planning and direction, are currently monitored through various citywide accountability mechanisms. These include:

- DYCD’s communication of its vision and mission through its official website and online media (outlined further under the Digital Government pillar), and indirectly through non-digital means such as flyers and worth-of-mouth;

- Any strategic priorities, policy statements, or other strategic planning or organizational documents that DYCD chooses to complete and promote, consistent with its Charter-mandated powers, or any other non-legislated reports or materials it may publish;

- Information on DYCD incorporated annually in the Charter-mandated Mayor’s Management Report (MMR);

- Performance evaluations conducted annually to assess the performance on City contracts– available via the “Procurement and Sourcing Solutions Portal (PASSPort)” operated by MOCS;

- Any information that DYCD provides during Council oversight and budget hearings held throughout the year (including in relation to the MMR);

- Statutory reporting obligations such as compliance under ‘open data’ laws, language access implementation, strategic planning under interagency coordination duties, accessibility plans, and State-mandated reporting, among others; and

- Dissemination of information and data as part of its mandated reporting obligations through an annual policy statement, and the strategic policy statement, respectively; or, through agency reporting to the Deputy Mayor of Strategic Initiatives.

For this review, DYCD provided some evidence of the internal processes it uses to monitor the agency’s strategic direction, and for communicating its direction through existing City accountability mechanisms. However, the agency provided almost no information on whether it has, or will have, a public-facing strategic planning framework (with actionable milestones), to guide its mission and vision, or to identify how the agency coordinates its priorities with the Administration and other agencies. There is room for DYCD to improve how it articulates its strategic vision to the public and to relevant stakeholders. Given the importance of stakeholders to DYCD’s mission, it could also benefit from periodically identifying, through a strategic plan or other tools, how it intends to manage and coordinate its efforts with the City, agencies, and relevant stakeholders, to achieve its desired aims.

- Strategy Development

Strategic development is important for helping agencies identify their priorities and connect them to measurable outcomes. Aside from DYCD’s general powers and duties noted above, it is not required to produce an overarching strategic plan, which gives the agency some discretion in deciding how it establishes and advertises its intended goals within the City’s existing accountability and reporting framework.

Since June 2022, Keith Howard has served as DYCD’s Commissioner. During this time, DYCD (one of the City’s largest agencies), has seen continued increases in its allocated funds, staffing levels, and the value of its contracts and interagency agreements. In its response to whether DYCD has an established long-term strategy, the agency cited its vision and mission, and noted that its strategic priorities are ultimately based on the Mayor’s and Commissioner’s priorities. DYCD identified its priorities as including:

- Integrating ONS;

- Timely contract payments to providers;

- Increasing its funding (from the State, federal sources, and philanthropy);

- Increasing its strategic partnerships;

- Increasing the marketing and promotion of the agency’s programs; and

- Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion.

In addition to these priorities, DYCD maintains strategic planning processes relating to performance improvements and policy development measures. These include agency evaluations of its data, and program evaluations conducted under DYCD’s Planning, Program Integration, and Evaluation (PPIE) division, and programmatic monitoring through its Evaluation and Monitoring System (EMS), a web-based platform accessible via the DYCD Connect system—an online portal for the public to access various information.

Aside from technical review processes, DYCD also produced annual reports (since at least 2014) although only the 2022 and 2023 annual reports are available through DYCD’s official reports webpage. As of the writing of this report there is no 2024 annual report. While these reports provide a high-level summary of the MMR, various agency highlights, and current initiatives, they do not articulate clear goal-setting priorities, or detail resource allocations for achieving them.

When reviewing the agency for this report, the Council heard from DYCD, advocates, and stakeholders, through a series of roundtables, meetings, and survey responses. From DYCD directly, senior leaders appeared knowledgeable and dedicated to identifying and setting new internal strategic priorities as an agency. While useful, transparency and accountability also demand that agencies work to ensure that their chosen strategies are aligning with public expectations. In this regard, stakeholders were consistent in wanting earlier and more consistent input from DYCD through better public sharing in the concept phase and more transparency around the agency’s short-term and long-term priorities—an aspect particularly critical given DYCD’s primary role as a contracting agency for CBOs and other external parties.

Unfortunately, and as addressed further under the Digital Government pillar, while DYCD clearly works hard to provide sophisticated and continuously improving online portals with relevant agency information, DYCD does not, at present, appear to have detailed publicly available information on its overarching long-term aims, or projected outcomes, as an agency. In answer to its approach on its long-term (or medium-term) strategic planning, DYCD–and the Administration–acknowledged its importance and pointed to internal ongoing processes to improve operations through an internal strategic plan (which was reported as being developed through the production period of this review). A toolkit for CBOs from the Community Resource Exchange, a key partner to DYCD as a technical assistance provider, also provides guidance directly on the importance of goal setting for strategic planning, indicating that DYCD views this strategic planning as important for the partners it uses to capacity build.

While regrettably the Administration did not make these internal strategies available to the review team, these efforts are nevertheless positive for DYCD, and something which should be continued. However, publicly available strategic planning remains an important component for improving agencies’ engagement, as public entities, with the constituents they serve, and the partners they rely on. For DYCD and the Administration, it is not sufficient to rely solely on other accountability mechanisms when the external partners DYCD relies on are asking for clearer strategic direction and stronger integration that incorporates their insights and expertise. A publicly available plan encourages engagement and scrutiny, and allows those supporters of an agency to closely monitor its direction and intended outcomes.

The Adams Administration’s reluctance for DYCD to produce such a plan is a missed opportunity for DYCD to demonstrate its internal efforts to strengthen its planning and outcomes. It also reflects poorly on an Administration presenting itself as transparent and efficient, while claiming to align DYCD’s priorities through the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Strategic Initiatives—which has minimal public or online presence.

There is an opportunity for DYCD to expand on its mission and vision through better articulating its strategic priorities through regular reporting. Setting these out with a measurable timeframe and the details necessary to achieve them, would assist CBOs and other stakeholders in understanding the agency’s aims, priorities, and constraints. This would also give DYCD an opportunity to routinely review its own overarching aims over each improving accountability for each review period. It could also help to provide better context for information in the MMR and other short-term reporting obligations, beyond that which is currently contained in DYCD’s annual reports. It could also assist both the Mayor in meeting their responsibilities under the Administration’s Charter-mandated strategic policy statement required every four years (an obligation the Administration is not currently meeting), and the Deputy Mayor for Strategic Initiatives in their strategic policy setting, by better understanding the long-term needs of the agency.

In Focus: DYCD’s Calendar Year 2025 Strategic Priorities Planning Process

While DYCD does not have a long-term strategic plan for the agency, senior officials from DYCD and the Administration met with the evaluation team to discuss the agency’s formulation and implementation of strategic priorities for calendar year 2025. The evaluation team heard how these strategic priorities focused on programmatic and operational priorities laid out by the Commissioner and further articulated goals and milestones to advance DYCD’s mission of alleviating the effects of poverty. While DYCD was unable to share the full strategic priorities document, senior agency officials briefed Council staff with a top-level overview of this process.

The evaluation team also heard how the process of compiling the strategic priorities for DYCD began in 2024 and was a revival of a process that the agency has undertaken many times in past years, although it had not been done since the second term of the de Blasio Administration. The stated intent of this process was to create an internal tracking and accountability document. Given the limited resources allocated to this project, DYCD noted that they were unable to expand the scope beyond one year, but will reevaluate this process for 2026.

When asked if DYCD engaged with public stakeholders throughout this process, DYCD mentioned that they would have liked to, but were unable, again citing limited resources. In terms of consultation with other City agencies or offices, DYCD referenced its relationship with DOE, noting that the agencies are already in alignment, and consultation with DOE was not deemed necessary.

While DYCD initially noted that this was solely an internal document with no plans for public release, when asked by Council staff if parts could be posted publicly, DYCD seemed amenable, stating that while “resources are tight, [this could be] something to consider with the resources available.” However, a senior Administration official questioned the need to publicize the agency’s strategic priorities, responding further that they did not see an agency or public benefit to the agency producing an agency-specific strategic plan. This response seemingly contradicts the Mayor’s stated commitment to “accountability, transparency, and effective governance.” The Administration official emphasized the sufficiency of “countless formal and informal touch points” for public engagement, and that this is an internal plan to achieve results and that the MMR publicly reports those results. As Executive Order 6 of 2022 states that “a free society is best maintained when the public is aware of and has access to government actions and documents, and the more open a government is with its people, the greater the understanding and participation of the public in government,” the Council strongly disagrees with the Administration’s views expressed to the evaluation team. Ultimately, the Council, with its Charter mandated power of investigation and oversight, benefits from performance reporting to help it better understand the activities of City agencies, including their service goals and management efficiency. Clearer reporting also helps to maintain public trust and confidence in City agencies by enabling better scrutiny by the Council, as the public’s representatives.

As DYCD undergoes a significant expansion for afterschool programs coupled with the first RFP for these programs in over a decade, the Council’s concerns regarding the strategic planning process and transparency are exacerbated. Bringing “together a cross-sector of leaders from community-based afterschool providers, advocacy groups, philanthropy, and the business sector” in an advisory capacity can strengthen the future of the programs. But delegating the responsibility of creating a strategy for this expansion to a new entity with an as-yet minimal public presence, rather than integrating it into a larger strategic plan for the agency charged with administering the contracts and providing support to CBOs and providers who are on the frontline, is yet another curious decision.

The Commission on Universal After-School, created pursuant to Executive Order 54 of 2025 is comprised of industry leaders who each bring to the table decades of experience. But with the day-to-day staffing of the Commission resting within the Administration, no formalized public feedback processes and public reporting of the deliberations and conclusions of the Commission built into the Executive Order, and the Administration’s expressed posture around transparency, the Council questions whether this is the most efficient and effective route for the formulation of this strategy. Further, given advocates’ concerns around communication and responsiveness raised throughout this report, there is a risk of this approach creating yet another separate channel of communication that CBOs and providers will have to navigate. The success of afterschool programs is paramount to the success of youth in New York City, and in pursuit of this goal, the Council supports a paradigm shift to one that centers and emphasizes transparency and collaboration, both public and institutional, in the strategic planning process to best support DYCD and its partners.

- Strategy Implementation

Effective strategic implementation should closely link to an agency’s strategic priorities, and appropriately integrate with all service delivery processes through a culture of continuous improvement. As noted, DYCD has broad authority to determine how it implements its overarching strategic direction, unlike with other duties including to produce a five-year accessibility plan, and language access implementation plan, where legislation prescribes what specific elements must be included.

Beyond the City’s broad accountability mechanisms, larger agencies develop a range of strategies to meet both their internal sub-divisions’ and the community’s needs. For this performance evaluation, aside from noting its mission, DYCD identified PPIE as integral to sub-agency contracting, serving as the bureau that codifies the required practices in its monitoring indicators and translates them into implementation. PPIE comprises several teams that work to integrate the network of programs DYCD oversees. These teams—not identified on DYCD’s publicly available organizational Chart—carry out various functions to advance DYCD’s capacity-building goals, with the agency implementing its plans through partnerships with its CBOs and internal agency divisions.

Being a large contracting agency that operates many different initiatives brings inherent challenges in communicating the agency’s efforts and achievements. As noted, while stakeholders generally agreed that DYCD meaningfully involves them in policy review process—from creation and implementation to monitoring and evaluation—they expressed a desire for greater transparency in how policy and priorities are set, how their feedback is incorporated, and ultimately, in understanding the rationale behind funding allocations and program evaluations.

As with its approach to strategic development, DYCD could address this by more clearly articulating a strategic plan that connects its core responsibilities to measurable priorities and sets timeliness for achieving them. This could then be used to feed back into its evaluations of progress towards program goals, providing more meaningful assessments of whether CBO partners are aligned with the agency’s aims.

DYCD could also benefit from using its strategic plan to identify all its responsibilities to the Mayor, other agencies, and stakeholders in relation to its intended operations (in accordance with its mandates), and linking those responsibilities to its priorities for each reporting period. To achieve this, the agency should expressly identify in its strategic plan every City agency, stakeholder, or other public or private partner the agency intends to co-ordinate with to achieve or contribute to its strategic priorities. If a sub-agency is operating under DYCD pursuant to legislation, the agency should define that sub-agency’s functions and what it will aim to achieve under its statutory mandates. The five-year accessibility plan and language access implementation plan are two examples of plans that already require more robust articulation of strategic priorities. Adopting a similar framework for an agency-wide strategic plan could help DYCD to better define its role, and that of its partners, in carrying out its strategic priorities.

Service Delivery For New Yorkers

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Equity | C |

| Access | D |

| Meeting Demand | D |

- Equity

Service and Resource Inclusivity

Inclusivity is a key aspect of people-centric services, and an organization must ensure that all services and programming are designed with a people-centered approach and accessible to all segments of the target population.

DYCD monitors all programs through site visits and provider feedback to ensure a safe and welcoming environment. It also implements an equitable investment strategy for site programs in areas of highest need, and staff receive training on accessible and inclusive engagement, including for people with diverse abilities and those with limited English proficiency. DYCD states that its expanding training for service providers and will include expanded topics, such as universal program design.

Inclusivity is also one of DYCD’s eight guiding principles, with the agency committing to “encouraging and inspiring the organizations [they] support to provide quality services to all communities, in safe, accepting environments with staff who are supportive, welcoming, and trustworthy.” In reporting on the progress made towards the agency’s equity goals, DYCD highlights that “Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities represent over 85 percent of program participants” and an expansion of “programs for young people up to age 24, NYCHA residents, and runaway and homeless youth,” among other achievements.

According to DYCD’s five-year accessibility plan, the agency is committed to ensuring its programs are accessible for those in the community that are differently abled. This is supported by its statement which reads

“At the New York City Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), we are committed to ensuring an inclusive and accessible environment for all our employees and our program and service participants. That means we’re committed to reducing barriers to accessibility for persons with disabilities, to have equal access to our resources and opportunities including in the workplace, and in the communities we serve. We understand that accessibility is essential to prevent discrimination and create a more inclusive and diverse workplace, which has been known to have positive effects on employee morale and productivity. Through this five-year accessibility plan, we are committing to taking proactive steps toward reducing or removing existing barriers”

Some advocates have raised concern that DYCD underserves youth with disabilities and lacks proper support and access that enables them to fully participate in DYCD programs.

At a 2023 joint NYC Council Oversight Hearing on After School Program Support for Students with Disabilities held by the Committee on Youth Services and the Committee on Mental Health, Disabilities, and Addiction, testimony submitted by INCLUDEnyc advocates for the importance of proper funding and care to support students with disabilities. According to hearing testimony, “Most publicly funded after school programs not operated by the Department of Education have limited experience supporting students with disabilities. Community-based providers often do not have formal training or experience working with students who receive special education services and do not have access to appropriate professional development opportunities. As a result, many community providers far too often cannot accommodate students with disabilities because they do not think they can appropriately support them with their existing staff and they do not receive funding to hire additional qualified staff, including paraprofessionals and nurses.” After-school providers also cited obstacles to supporting youth with disabilities due to a lack of coordination and sharing of information with school providers on student Individualized Education Programs and relevant accommodations.

Paraprofessionals are employed by DOE and CBOs to work with students in after school programs, including students who are differently abled or require other forms of care. Paraprofessionals provide crucial support to afterschool programs and can offer more individualized and direct support to students, allowing students with disabilities to receive personalized attention from providers. Testimony submitted by United Neighborhood Houses at the DYCD 2026 Executive Budget Hearing held on May 19, 2025, states that funding for paraprofessionals is needed. The CBO encourages DYCD to work with providers to develop a plan for serving youth with disabilities in COMPASS and “School’s Out New York City” (SONYC) programs.

A 2024 Council roundtable and survey with DYCD providers and advocates revealed that DYCD programs and services underserve some vulnerable subpopulations. According to After-School, Adult Literacy, and RHY advocates, migrant communities face barriers to accessing many DYCD programs due to shortages of multilingual staff and public transportation options from program sites to migrant shelters. Additionally, advocates stated that Adult Literacy program funding was cut by 35 percent last year, and the contract amendments were unfavorable for providers.

Many CBOs face challenges in extending services to all eligible or interested community members due to insufficient funding; specifically, some community development organizations located outside specific Neighborhood Tabulation Areas (NTAs) cite receiving significantly less support than other CBOs in neighborhoods despite similar community needs. RHY providers also reported dramatic underfunding.

While DYCD serves many marginalized communities, extensive feedback from providers and advocates on barriers to access faced by distinct subpopulations suggests that DYCD programs are not yet accessible to all segments of the population.

- Access

Availability of Resources and Assistance

The agency states that providers and participants use the discover DYCD portal to find nearby programs. This process is the agency’s primary means of informing the public of the resources available to them in their area.

It is important to note that DYCD’s web platform, which enables the public to search for and apply for DYCD programs, states that “DYCD-Funded services are offered free of charge except for Discretionary funded services where providers had informed Council as part of their application that they would be charging fees and obtained prior written approval from DYCD.” Accordingly, most DYCD-funded programs are offered at no charge.

DYCD partners with DOE to provide free summer enrichment programs to K-8 public school students, administered by COMPASS and Beacon providers. In the summer of 2024, more than 115,662 public school students participated in and benefited from these programs. COMPASS consists of 890 programs serving youth enrolled in K-12. K-5 students are offered literacy instruction, homework help, essential arts, physical activity, national programming, and more, 5 days a week, including school holidays and summer. Beacon providers serve 92 school-based community centers that work with children aged six and older, as well as adults. These programs operate during non-school hours and typically include activities such as academic enhancement, life skills, career awareness, civic engagement, recreation, fitness, and cultural enrichment.

It is crucial to consider that timing significantly influences access and the availability of resources. For instance, the FY26 Adopted Budget added 100 beds for DYCD’s RHY youth program for individuals aged 21 to 24. This would increase the total number of beds available for this age group to 160. During a Council oversight hearing on RHY held on June 21, 2022, advocates expressed an urgent need for more beds, stating that the existing 60 beds for older youth were inadequate. Although the increase in beds is a positive development for DYCD and the community, the lack of progress over the past three years has left this age group without sufficient access to resources in the meantime.

Supplying resources in a timely manner is important when meeting the needs of communities because it equips providers with the tools necessary for service delivery when the moments are most impactful or prevalent. Significant delays in funding, program implementation, and resource expansion further aggregates existing struggles and gaps in these services. While DYCD eventually meets many demands, there is a disparity of support for vulnerable populations during the waiting period that can lead to a lack of efficient care for these communities when they need it most.

While the Council recognizes resource constraints and agency obligations that contribute to the reduced availability of resources in a timely manner, it is incumbent upon the agency to prioritize the pressing needs of those they serve, especially the most at-risk. As discussed earlier in this report, a public facing strategic policy statement and accompanying implementation plan would highlight the agency’s aims, priorities, and constraints and allow the Council, CBOs, and other partners to better react to deficiencies where identified.

Selected DYCD Programs

In Focus: Runaway and Homeless Youth

“The New York City Department of Youth and Community Development funds services for Runaway & Homeless Youth that include Drop-in Centers, Crisis Services Programs, Transitional Independent Living programs, and Street Outreach and Referral Services.” All programs offered by RHY are free and cover a proportionate range of needs to address the key issues facing their target beneficiaries.

These programs include:

- Transitional Independent Living

- Crisis Services Programs

- Borough-Based Drop-In Centers

- Street Outreach

DYCD identifies its target beneficiaries of its programs as individuals aged 16-24. The first two programs (Transitional Independent Living and Crisis Services Program), DYCD divides this group into two age groups, one for individuals aged 16-20 and the second for those aged 21-24. Program locations and contact information for Crisis Services, Borough-Based Drop-In Centers, and Street Outreach are available on the DYCD website.

These programs play a vital role in supporting at-risk youth with resources that touch topics of education, job security, housing security, mental health management, life skills, and housing reunification. Even so, RHY, as a whole and divided amongst its programs, has inefficiencies that create accessibility issues for the communities they aim to serve. Despite the additional 100 beds for the program ultimately secured in the FY26 Adopt Budget, testimony by advocates at the FY26 Executive Budget Hearing, held on May 19, 2025, highlighted that existing drop-in shelters are still consistently underfunded and understaffed. Additionally, because the bulk of DYCD’s mental health related programs are housed within RHY, there is additional concern of underfunding for drop-in centers that provide free counseling and emotional support.

In Focus: Cornerstone

“Cornerstones provide engaging, high-quality, year-round programs for adults and young people. Programs are located at 100 New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) Community Centers throughout the five boroughs.” The program began in 2010 at 25 NYCHA Community Centers and has since expanded to 99 NYCHA Community Center locations throughout the five NYC boroughs. All programs are free and cover a wide range of topics.

Youth program areas typically include:

- Academic Supports

- Life Skills / Interpersonal Skill Development

- Healthy Living

- High School and College Prep

- Project-Based Activities

- Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM)

- Creative and Performance Arts

- Entrepreneurship

- Youth Councils

These programs are for ages 5-21 and have both summer enrollment (early spring) and school year enrollment (Elementary Aug-Sept, all others, year-round)

Adult program areas typically include:

- General Educational Development

- English for Speakers of Other Languages

- Parenting Skills

- Workforce Development and Referrals

- Family Relations

- Tenant Education and Advocacy Cultural Activities

- Computer Access and training

- Intergenerational programming

- Cultural Activities

These programs are for ages 21+ and have both Summer Program Enrollment (April) and School Year Enrollment (Aug-Sept).

Program location and contact information can be found on https://discoverdycd.dycdconnect.nyc/home.

These programs play a vital role in supporting the City’s communities with resources and opportunities, but providers continue to face challenges. During the DYCD 2026 Executive Budget Hearing held on May 19, 2025, Commissioner Howard discussed ongoing talks with other City agencies, such as the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), about expanding these programs. As of 2025, Cornerstone contracts have not been updated in ten years. At the same hearing, Deputy Commissioner of Youth Services, Susan Haskell, testified that there are currently 100 Cornerstone programs.

In Focus: Comprehensive After School System of New York City (COMPASS) and School’s Out New York City (SONYC)

COMPASS is a program for young people enrolled in grades K-12. It gets young people to participate in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) learning, arts and sports programming, and skill-based work to “support academic achievement, raise confidence and cultivate leadership skills through service learning and other civic engagement opportunities.”

For students in grades 6-8, DYCD’s middle school program SONYC provides youth with after school programming in a variety of activity areas. SONYC provides “rigorous instruction in sports and arts; and requires youth leadership through service.”

In April 2025, New York City made a historic $331 million investment to advance Mayor Adams’ vision of “After School for All,” aiming to provide access to afterschool programming for all public school students from kindergarten through eighth grade. This commitment, which will total $755 million in annual funding, supports the phased addition of 20,000 new after-school seats over three school years. Beginning in Fiscal Year 2026 (FY26), 5,000 new seats will be added to existing COMPASS programs, followed by an additional 10,000 seats in Fiscal Year 2027 (FY27) and the remaining 5,000 in FY28. These programs provide critical enrichment activities after school, during school holidays, and in the summer—supporting the academic, social, and emotional development of K–8 students while providing essential childcare for working families.

In anticipation of this expansion, DYCD released a concept paper outlining the framework for upcoming RFPs for COMPASS Elementary and SONYC programs, released on October 1, 2025. Advocates have voiced concerns that the proposed year-round price per participant rates of $6,800 do not account for inflation and Cost-of-Living Adjustments (COLAs) over the grant period. Furthermore, the rate is insufficient for full-year elementary-school aged programming when including all described program elements and with staff child ratios. The Committee on Children and Youth held an oversight hearing on September 18, 2025, to evaluate the goals, structure, provider feedback on DYCD’s proposed program design, and implementation plan.

In Focus: Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP)

SYEP, established in 1963, is one of DYCD’s many youth programs and one of the largest youth employment programs in the country. SYEP was designed to connect New York City youth, aged 14 to 24, to career opportunities and paid summer jobs to better prepare them for future careers.

SYEP offers various programming depending on your age and background. Youth aged 14 to 15 receive a summer stipend to participate in project-based learning activities that benefit the community and provide them a chance to explore career opportunities. Youth aged 16 to 24 are set up with a paid summer job or internship in industries such as fashion, technology, arts, healthcare, transportation, real estate, and hospitality to improve their work skills and engage them in exploring various career paths. SYEP participants who face certain employment barriers are eligible for the Emerging Leaders program, which provides more specialized experiences. Participants must face at least one of the below barriers to qualify for eligibility:

- Homeless or runaway youth

- Justice-involved youth

- Youth in or aging out of foster care

- Receiving preventative services through the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS)

SYEP prioritizes youth who come from underserved communities and face various barriers to job opportunities. Due to SYEP’s limited number of spots, DYCD actively de-enrolls SYEP participants who fail to complete key work readiness tasks before July 1st so that they are able to open those slots to other youth they feel might better benefit from the opportunity.

The FY25 Preliminary Budget included $225 million for SYEP, 6 percent less than the FY24 Adopted budget. At adoption, the FY25 included $234.8 million for SYEP. The FY26 Adopted Budget included $243.5 million for SYEP, a 3.71 percent increase over the FY25 Adopted Budget.

In FY25, SYEP received 183,363 applications but was only able to fulfill about 53 percent due to limited availability of program spots. SYEP has grown by almost 30 percent over the last three years, from 74,884 participants in Fiscal Year 2022 (FY22) to 97,004 participants as of the FY25 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report (PMMR). Despite DYCD’s statement in their SYEP program description that SYEP opportunities are paid, only about half of all participants in FY25 received stipends or wages, totaling close to $140 million.

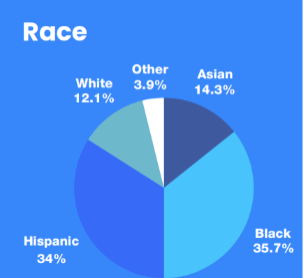

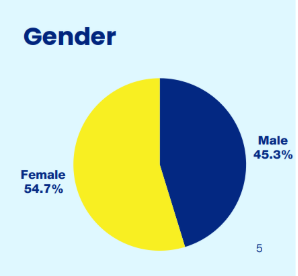

The most recent Annual Summary report for SYEP highlighted that the majority of SYEP participants, 62 percent, came from Brooklyn and the Bronx and participants were either largely Black or Hispanic (36 percent and 34 percent respectively), and majority female, 55 percent. See below for the full breakdowns:

In Focus: The Fatherhood Initiative

According to DYCD’s 2016 Fatherhood Initiative Concept Paper, in New York City, about 22 percent of children are being raised in homes without fathers. When fathers are actively involved in the lives of their children, their children perform better in school, are more likely to be emotionally secure, and more likely to exhibit self-control and prosocial behavior. The Fatherhood Initiative, which was contracted separately from DYCD’s other Family Support Programs, is designed to promote responsible fatherhood. The program was created to help low-income, non-custodial fathers improve their relationship with their children through increased engagement with them as well as increased financial support. The initiative offers resources to three groups of fathers: fathers ages 16 to 24 (“young fathers”); fathers 25 and older (“older fathers”); and fathers with prior involvement in the criminal justice system (“justice-involved fathers”). Contractors serve a minimum of 180 and a maximum of 210 fathers annually in three cycles of 60-70 participants each. Once participating fathers have received three months of program services, they then receive three months of follow-up services.

DYCD Fatherhood programs are designed to address five core areas: 1) parenting skills; 2) effective co-parenting with the child’s guardian; 3) employment and education; 4) child support; and 5) visitation. Staff use a strengths-based approach and work with the participant towards goals identified by the participant through workshops, support groups, and other activities. The programs incorporate principles of positive youth development, family engagement, social and emotional learning, and youth leadership, which the participants can in turn apply in their relationships with their children.

Fatherhood program participants are recruited in a multitude of ways. In some cases, participants are required to complete the program as part of a court order. In others, caseworkers from New York City agencies or outside organizations refer those who they believe could benefit from the program. Referral sources may come from ACS, legal services, foster care, and nonprofit organizations. According to a 2016 study of the program by Policy Studies Associates, Inc., a total of 2,952 men enrolled in the Fatherhood Initiative from July 2012 to June 2015. While participants reported benefitting greatly from the services offered through the program, several recommendations emerged from the study:

- Offer more differentiated services;

- Expand services to address basic needs of participants;

- Systematically offer legal services and support for navigating the legal system;

- Provide more options for programs for mothers or joint workshops with co-parents;

- Expand education and employment supports;

- Focus on retention; and

- Create more structured supports for alumni.

Mitigating and Reducing Program Barriers

DYCD highlights its feedback collection process and community engagement as its primary means of forging a path forward to make programs more accessible and eliminate existing barriers.

The agency states that they conduct a series of surveys for participating to determine why a specific accessible need was not met.

The choices range from:

- The program was too far away

- I did not know where to go

- Costs too much

- Programs not offered during a time when they could go

- Turned away/waitlisted by the program

- Not provided in their language

- Poor quality of service

- I did not know help was available

- Other

Moreover, DYCD responds with similar reasoning and processes for various agency and programmatic solutions and improvements. In correspondence with DYCD, a consistent theme emerged regarding the use of community and provider feedback to guide their programs and the actions they take as an agency, with the caveat that these factors held strong influence but were not final deciders; other factors, such as funding and jurisdiction limitations, took precedence. However, further analysis shows minimal and underdeveloped improvement across programs over the years. Discussed in more depth in the metric analysis pillar of this report, previous MMR statistics paired with advocate feedback suggest that DYCD’s plan to mitigate and reduce programmatic barriers moving forward is underdeveloped.

Several indicators provided in the MMR support advocates’ claims by demonstrating a lack of growth and goal adjustments. Additionally, the agency records most of its CNAs within RFPs, which are minimally updated, further supporting advocates’ claims.

- Meeting Demand

Referral Processes

For an organization to meet the highest standard of service access, it must have processes in place to refer clients to alternative services if it cannot provide them with the services directly due to ineligibility or lack of capacity.

DYCD conducts referrals of services and programs through public outreach and intake processes. DYCD states that they refer individuals to certain programs based on their respective needs and prioritize ensuring that community members have access to information and their programs.

The agency also states that they rely heavily on word of mouth and CBOs referring clients to services and programs. Advocates claim that they often refer individuals to other CBOs and programs depending on the specific services they need.

Continuity of Services

Continuity of services can be understood as an individual receiving services at the same location from the same provider or the seamless delivery of services through the referral, coordination, and integration of information among different providers. While services provided at the same place by the same provider is optimal, it is recognized that a single provider can rarely meet all of an individual’s needs.

Continuity of services depends on several variables including location, income, eligibility, and funding. Provided these criteria are met, individuals within specific locations should be able to access their local programs regularly. DYCD states that they prioritize ensuring programs meet the community where they are and are consistently accessible for those utilizing their resources.

On the other hand, certain advocates claim that there is a lack of continuity in DYCD’s specific processes for programs. For instance, at a joint oversight hearing on Summer Rising by the Council’s Committee on Children and Youth and Committee on Education held on October 30, 2024, a local advocate testified that “there is no continuity under the current enrollment process. Parents and students are upset that when they are offered summer rising slots, it’s often in an unfamiliar school or an unfamiliar CBO.” In fact, one CBO that offers summer programming through Summer Rising, provided testimony that the enrollment process “would be far more effective if schools and CBOs could collaborate and support families in enrolling in a summer program that meets their children’s needs.” The CBO continued that in its “observation over the past four summers […] families dropped out of Summer Rising at rates far higher to rates [it] saw prior to Summer Rising, when the city funded CBOs to run full-day camps and allowed them to control the enrollment process.”

Service delivery varies across programs and individual experiences; as such, it can be challenging to ensure continuity of care with multiple elements involved; however, the agency still has a responsibility to provide individuals with consistent and accessible programs and resources to the best of their ability.

Ensuring Communication and Support

An essential aspect of service accessibility and client prioritization is guaranteeing that agency support is available to all clients through various channels.

In a Council roundtable with advocates, many expressed that the feedback collected by DYCD is not used but is rather perfunctory. Many claim that DYCD is unreachable, makes minimal effort to return phone calls and emails, provides no information on how their feedback is being used, and has not seen their feedback implemented for growth. Furthermore, their claims related to contract concerns and non-payment issues are often met with no response. Advocates state that the agency has also eliminated their in-person feedback sessions and heavily restricted their Zoom sessions, which are also described as unhelpful. Out of 37 of advocates surveyed and met with, 27 percent agreed that DYCD’s feedback process and communication with CBOs is lacking. Providers claim that their feedback and communication process is not used to benefit the agency or their contracting process. This directly contradicts DYCD’s claim that provider input and communication are one of their primary sources of agency and program improvement.

When this topic was addressed during a meeting with DYCD, the Council inquired about managerial oversight on program managers, to which the agency stated that there is not a significant amount. According to the agency, program and case workers are not monitored when they reach out to a provider or fail to do so. There is no tracking process for timely responses to inquiries from providers, and there is limited accountability to ensure that program managers communicate with providers consistently and thoroughly. As a result, providers report that their calls and emails are rarely answered, and their program managers are difficult to contact.

Relationships and Collaboration

The Relationships and Collaboration pillar assesses how inclusive the agency’s policy design and improvement processes are. This review also assesses the agency’s effectiveness in collaborating with external partners, as agencies frequently work with outside stakeholders, including CBOs and other governmental agencies, to achieve shared objectives. The evaluation is conducted with an understanding that positive working relationships and collaboration are contingent on outside partners’ willingness to work with the agencies.

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder Engagement | D |

| Institutional Engagement | C |

- Stakeholder Engagement

Feedback Processes

The Human Services Quality Framework, created by the Queensland Government in Australia, outlines how an accessible and effective feedback and complaint process is critical to an organization’s implementation of service delivery improvements. Under the framework, the Human Services Quality Standards state that organizations should establish “fair, accessible and accountable feedback, complaints and appeals processes & client complaints” and demonstrate how these processes lead to service improvements.

The DYCD website has a customer satisfaction survey section that states, “Our goal is to serve the public through an informative and helpful website. We want to hear from you! Please answer all questions. Your comments will help us better meet your internet needs.” The survey comprises ten multiple-choice questions, two toggles, and one open-ended question. It is important to note that all questions relate to the user experience of navigating the DYCD website, not DYCD services. Additionally, there is a separate section where one can write an email to the commissioner about a topic of their choosing; here, they can address any concerns they may have, though this is not a formally documented form and is instead an automated message system. The ‘Notice of Rights’ section contains information about the grievance procedure under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

According to the agency, “DYCD conducts stakeholder engagement as part of the program planning process before concept papers and proposal requests are developed and released. This includes surveys or focus groups with participants of our programs, including youth. In addition, some program areas regularly conduct feedback surveys with participants during the program (e.g., SYEP).” When speaking with advocates and local CBOs contracted with DYCD, concerns were raised about a lack of outreach regarding user feedback and complaints, particularly in response to input from the CBOs. In addition to a lack of outreach, there is uncertainty about where the minimal amount of collected feedback goes and how it is implemented, as stated above.

DYCD highlighted a Community Needs Assessment that they use to engage stakeholders and collect feedback from community members. According to the agency, “DYCD collects feedback from community members in 41 designated geographic districts known as Neighborhood Development Areas (NDAs) about the programs and services needed in their community. DYCD implemented this process to hear directly from New Yorkers and document views on what is needed to improve the well-being of their communities.” However, there is still minimal understanding of how this information is utilized to advance programs and enhance existing infrastructure.

According to DYCD, they utilize Community Boards to facilitate community feedback and development. “Neighborhood Advisory Boards (NABs) allow residents to participate in the community development planning process and help guide New York City in allocating federal CSBGs anti-poverty funding which supports community-based human service programs in areas such as youth education, employment, housing, immigrant services, literacy, and senior citizen services.” The NABs are aligned with the 41 NDAs.

While collecting feedback from neighborhoods with more vulnerable communities that have higher or more specific needs is imperative, it is unclear how outreach is conducted to neighborhoods not deemed an ‘NDA’ and what resources they need.

Participation

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has established frameworks that provide a public governance approach to policy, addressing the unique and specific needs of vulnerable populations. The frameworks can assess programming and engagement with populations, prioritizing “focused activities to promote participation and feedback from vulnerable and marginalized groups.” The OECD further suggests that organizations “involve relevant stakeholders at all policy process stages, from the elaboration and implementation to monitoring and evaluation.”

According to the agency, DYCD collects feedback from New Yorkers aged 14 and up and community members in the 41 NDAs about programs and services needed in their communities. This feedback, along with feedback from NDA residents and the NABs, informs the community development planning that helps guide DYCD in fund allocation.

DYCD reiterates that they conduct exclusive stakeholder engagement to inform the NDA program models. This feedback is elicited through various focus groups and meetings with DYCD and non-DYCD-funded providers, City staff, and local experts. DYCD providers also complete surveys, and interviews are conducted with providers who withdrew their contracts before the end of their contract agreement to learn more about the administrative and operational reasons for doing so.

As previously stated, advocates once again expressed they had minimal knowledge of how their feedback is used in the program planning and budget process.

In Focus: Improving New York City’s Youth Board

Local Law 32 of 2025 relating to the composition of the youth advisory board sponsored by Council Member Althea Stevens, Chair of the Committee on Children and Youth, was enacted on March 29th, 2025.

The Youth Board (YB) is group of younger individuals who provide input and insight into NYC youth programs and policies. According to the legislation, “this bill would require that appointments or recommendations for youth board members must be made with best efforts to ensure that appointees have demonstrated relevant experience in the area of youth welfare. Additionally, this bill would require that to the extent practicable, at least 3 members of the board be between the ages of 16-24, in order to ensure actual youth representation.”

The purpose of this bill is to ensure the YB has representation by individuals with firsthand experience in areas related to youth welfare, so that their recommendations and input align accordingly with the needs of youth in New York City. Their recommendations will benefit DYCD funded programs by advocating for needed changes and program expansion.

Awareness within New York City Communities

DYCD regularly partners with the My Brother’s and Sister’s Keeper Youth Leadership Council, formerly the Mayor’s Youth Leadership Council. This organization allows youth aged 16-24 to inform City policies and practices, as well as DYCD programs. The agency states that it engages with various youth councils, youth collectives, youth groups, and the NYCHA Youth Advisory Boards.

The CNA is a stakeholder engagement process through which DYCD collects feedback from New Yorkers aged 14 and up to gather insight on programs and community needs. DYCD states that it aims to have representation from diverse experiences, demographics, and types of providers. For example, for CNA Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23), DYCD conducted an engagement process collecting feedback from 28,751 residents across 41 NDAs. The survey questions focused on areas where community members felt their needs were not being met: these included food and nutrition assistance, healthcare, mental health access, financial assistance, immigration and citizenship support, legal services, transportation needs, housing assistance, and more. Reasons from program location, cost, language barriers, and lack of program visibility were all factors that contributed to individuals struggling to have their needs met. DYCD states that the results of this survey demonstrated the demographics of NYC: 31 percent of respondents identified as Black or African-American, 27 percent as Hispanic, 26 percent as Asian, and 23 percent as White or Caucasian. The CNA response indicated more than 14 primary languages spoken within the home; English was reported at 61 percent, Chinese at 19 percent, and Spanish at 13 percent. According to the agency, these findings help inform critical strategic initiatives and new agency directions, such as internal decisions and policy-making processes.

Despite these outreach efforts from the agency, many community members report having minimal knowledge or awareness of DYCD’s programs. This statement is directly supported by DYCD’s 2023 CNA report, which is also the most current report available to the public. The report states that “the most frequent reason was that they did not know where to go to access services, 43 percent (43%). In addition, at least 20 percent (20%) of respondents said that they didn’t know that services were available.” Nearly 29,000 people across all five boroughs responded to this 2023 CNA report.

DYCD’s awareness of the community’s lack of knowledge of agency programming lacks meaning without consistent efforts to address said lack of awareness. When asked about initiatives to advance these efforts, DYCD provided answers using the exact outreach tactics employed before this report was published, which indicates a lack of intention to expand community program awareness. However, the Council recognizes that directing more awareness to existing programs may be counterproductive if not accompanied by an associated increase in capacity and funding for these programs.

In Focus: DYCD’s Concept Paper and Stakeholder Engagement

As part of the City’s procurement process, and pursuant to section 3-03(b)(1) of the Procurement Policy Board Rules, the concept paper and subsequent public feedback and comment process provide a significant avenue for stakeholder engagement prior to an RFP. For DYCD’s COMPASS and SONYC programs, given that the RFPs released on October 1, 2025 represent the first of its kind for over a decade and announced expansion of these programs, the stakes and importance of the concept paper and feedback process were exponentially greater.

According to testimony from Deputy Commissioner Susan Haskell at the September 18, 2025 Committee on Children and Youth Oversight Hearing on Afterschool Programs and DYCD’s Concept Paper, “[b]etween May 30 and July 11, DYCD conducted a robust stakeholder engagement process on the Concept Paper. DYCD facilitated 14 feedback sessions with 272 stakeholder attendees including providers, advocates, arts organizations, parent leaders, and most importantly, the young people themselves.” Furthermore, Deputy Commissioner Haskell testified that DYCD “intend[ed] to incorporate stakeholder input into the RFP” released on October 1, 2025.

A stakeholder engagement section was included in the RFP, which states:

“In developing the RFP, DYCD responded to stakeholder feedback to the Concept Paper on a variety of issues. For example, regarding programmatic elements, DYCD clarified the new mental health requirements, provided details on [Social and Emotional Learning] as a required content area, and enhanced language around Arts Programming and Career/College options. With respect to staff qualifications and experience, DYCD responded to input regarding alignment with the New York State School Age Child Care (SACC) requirements, and to feedback on the professional development requirements. DYCD also took account of stakeholder input on subcontracting, and access to resources and supports to meet the needs of students with disabilities.”

The RFP kept price per participant rates at $6,800 for elementary students and $3,900 for middle school students. At the aforementioned September 2025 hearing, providers and advocates shared a consensus that these rates continued the trend of underfunding, with Children’s Aid noting that [u]nder these…rates, COMPASS and SONYC providers will recover roughly sixty to seventy percent of program costs in the first year, with this gap only widening as expenses rise over time.”

The Council recognizes that DYCD alone cannot unilaterally set price per participant rates, as noted by DYCD leadership, and requires support from the Administration and OMB. Yet, the unamended price per participant rates, despite unified feedback about their inadequacy, and the lack of explanation in the stakeholder engagement section of the RFP, represent yet another instance in a long line of failures by City Hall to put CBOs and providers in a necessary and sufficient position to best serve the youth of New York City. As public testimony supports, this will pose challenges for the incoming Mamdani Administration and provides an opportunity to rectify this failure through more transparency, additional stakeholder engagement, and possible contract amendments. It is time for the Administration and OMB to have meaningful discussions with CBOs and providers on the math behind these rates and show their work.

- Institutional Engagement

As outlined in the Human Services Quality Framework, strategic agreements and partnerships are essential for an agency to work effectively with community networks, other organizations, and government agencies, and thereby achieve its desired outcomes.

Agency Collaboration with Other Governmental Agencies

DYCD collaborates with various City agencies to reach shared goals and projects. The agency collaborates closely with DOE for school-based programs, meeting regularly with their staff and working with additional City agencies to establish Requests for Proposals (RFPs). When inquiring with DYCD about their relationships with other agencies, the Council asked the following question:

How does DYCD collaborate with relevant community support networks, other organizations or government agencies? Please provide at least two examples.

To which the agency responded, “DYCD’s collaboration efforts differ depending on the program types. One example is our close collaboration with DOE for our school-based programs which includes regular meetings and coordination with their staff. DYCD also engages community networks, providers and city agencies in preparation for concept papers and RFPs. In addition, DYCD engages with an organization in networking events and town halls.”

With significant overlap between the goals of DYCD’s youth educational and enrichment programming and DOE, this close collaboration is expected. But advocates have noted a need for further collaboration between these agencies, particularly as it relates to data sharing, joint data analyses, and collaborative public reporting of data. To address advocates’ long-standing transparency concerns on afterschool program data, the Council passed Local Law XX of 2025 on September 25, 2025. This local law requires DYCD and DOE to “each submit annual reports on the afterschool programs they offer, as well as those offered by their respective contractors. Specifically, DYCD and DOE would be required to report on program location, available seats, enrollment, student demographic data, and average attendance rate for each afterschool program offered in the previous school year.” This legislation intends to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the utilization of afterschool programs in the city, and to allow for publicly informed, data-driven decisions about the future of these afterschool programs. The reports required by this legislation are to be produced annually, with the inaugural reports from DYCD and DOE due no later than August 15, 2026.

While the Council appreciates the collaboration between DYCD and DOE, and encourages further collaboration and coordination, based on testimony during the September 18, 2025, Committee on Children and Youth Oversight Hearing on Afterschool Programs and DYCD’s Concept Paper, greater transparency and more work is needed by each of these agencies, particularly as it relates to site selection, students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) and specialized needs, student transportation, and coordination and alignment. Added transparency behind decision-making, operational coordination, and data on student outcomes, amongst others, will only strengthen these programs that are critical to the success of youth in New York City.

When asked about their relationship and collaboration with MOCS, DYCD responded, “MOCS is an oversight agency for all procurement and contract related matters. As an oversight, MOCS provides guidance, reviews and approves procurements released by DYCD and approves awards made on any competitive solicitations prior to provider notification. DYCD meets with MOCS on a weekly basis to discuss any procurement and contract related matters.” DYCD provided no further information on their collaboration processes with additional agencies.

Additionally, while the Council understands difficulties and challenges presented by this first iteration of its Report Card Initiative, the production of the report for DYCD faced additional challenges from the Eric Adams Mayoral Administration not seen during the production of the reports for the Departments of Parks and Recreation and Veterans’ Services. Not only were requests for comment and feedback significantly delayed by months, but the information, when finally provided, was vague and lacked detail. The Council made multiple attempts to reach out to DYCD, connect with them, set up meetings, and tried to ensure they had an active voice throughout this process. The Council was rebuffed in its efforts and requests were ignored and efforts disregarded. As the goal was to establish a mutually beneficial partnership with the agency, the Council has conducted its due diligence in maintaining these efforts. As such, the Council does recognize efforts made by managerial staff within DYCD to foster collaboration and communication. When meetings were scheduled and attended, the Compliance Division and DYCD staff had productive, helpful, and effective discussions. These meetings resulted in a more thorough and collaborative analysis across several pillars, whereas the lack of communication led to the opposite. As a result, this report is not as in-depth as initially intended. (See Timeline).

In Focus: DYCD and Ancillary Offices

As part of the inaugural round of the Council’s Report Card Initiative, the evaluation team met with ancillary offices throughout the Administration that impact or support the work of the assessed agencies, including DYCD.

Established pursuant to Local Law 62 of 2021, the Mayor’s Office of Sports, Wellness and Recreation (MOSWR) is “charged with the authority to promote and enhance sports-related opportunities for youth and to promote the role of sports in education” and requires regular consultation with other city agency leaders, including the Commissioner of DYCD. The position of Director of Sports, Wellness and Recreation has been vacant since September 26, 2025, and the office was previously led by Jasmine Ray, who was appointed on December 27, 2022.

In meeting with the evaluation team, MOSWR noted that while the Office did not have its own dedicated budget and minimal staff, it was able to reestablish the Mayor’s Cup, a series of “competitions includ[ing] basketball, wall ball, pickleball, robotics, dance, e-sports, and volleyball,” and hold other events with financial support from DYCD and private sponsorships. The MOSWR website lists eight Mayor’s Cup events held between 2023 and 2025, although an unlisted relay event held on January 21, 2025, at the Armory in Washington Heights is posted on the Office’s Instagram page.

Given the current leadership vacancy, extremely limited resources, and minimal reach of MOSWR, this presents a tremendous opportunity for the next Director of Sports, Wellness and Recreation to establish a new, comprehensive strategic plan for the Office to complement DYCD’s goal of providing “a wide range of high-quality youth and community development programs,” and support “furthering the City’s commitment to health, wellness, and social development through extracurricular and school-based sports and recreation programs.”

Workforce Development

The Workforce Development pillar focuses on the agency’s staff capacity, training, and development. This review assesses the agency’s effectiveness in maintaining its headcount, training and developing its staff, and ensuring that staff members are reflective of the communities they serve. This pillar is evaluated with the understanding that the agency maintains and develops its staff using the resources available to it.

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Staff Capacity | C |

| Staff Development | A |

- Staff Capacity

Proportionate Staff Levels and Retention

Staff capacity can indicate an agency’s ability to meet the needs of its community, particularly in human service organizations that serve vulnerable populations. Ensuring that staffing levels are sufficient and proportionate to the community’s demonstrated need is essential for effective service delivery. DYCD has shared that program managers oversee programs based on location rather than specialty. Multiple programs within a specific area will be assigned to a program manager, who will be responsible for oversight of these programs and their respective providers.

Advocates expressed concern about DYCD’s staff capacity. Some argue that the number of DYCD programs or case managers is insufficient for the number of CBOs contracted, resulting in a ratio of one case worker assigned to multiple programs at DYCD. This leads to less attention and responsiveness for each program. Despite numerous attempts to obtain a specific program-per-manager ratio from the agency, it remains unclear how many programs each manager is assigned and whether program manager capacity is adequate. DYCD notes that the variance of workload ratios is best described as a “bit of a range,” given the differences by program; as an example, SYEP was described as a “six-month intense cycle,” and that other programs require a “lighter touch.” Given the concerns raised by advocates and the difficulty for the agency to quantify staffing ratios, there is a large opportunity for DYCD to improve its staff capacity and ‘customer service’ perception by partnering organizations, beginning with a thoughtful, comprehensive review of workload allocation and internal procedures.

DYCD is a contracting agency, CBO staffing capacity is often directly related to or impacted by DYCD’s contracts. During a Council roundtable with CBOs and advocates on this report card, it was stated that CBO staff are often underpaid due to the amount of money allotted to staffing in their DYCD contracts. The agency has mandatory staffing ratios, but low wages often result in staffing shortages within CBOs. As a result, CBO employees are working overtime to maintain program efficiency, and their current contracts do not allow pay for overtime work because staffing is already underfunded.

The agency states that CBOs did get a COLA on July 1, 2024. This announcement followed a statement from Mayor Eric Adams’ Administration on March 14, 2024, in which Mayor Adams stated that a $741 million investment would be made for an estimated 80,000 human service workers employed by non-profit organizations with a city contract, as part of a new COLA. In the FY25 Executive Plan, funding for the human service provider COLA was baselined across agencies with such contracts and included an increase that was already baked in for future years. For DYCD specifically, $13.8M was added in FY25, increasing to $28M in FY26, and then increasing to $42.7M in FY27 and years beyond. It is the Council’s understanding that this COLA has been implemented by agencies.

DYCD is largely a contracting agency, with roughly two-thirds of the agency’s budget allocated to contracts, the Council felt it was appropriate to evaluate staff capacity from the perspective of CBOs. The Council recognizes that CBO staffing is heavily affected by the budget DYCD is allocated, and that the Administration has implemented COLAs to rectify non-profit staffing shortages and low wages. However, it is still incumbent on DYCD to ensure that all CBOs have the support necessary to operate programs efficiently and to utilize all available resources and tools to address these ongoing challenges.

- Staff Development

Recruitment

Organizations should establish “transparent and accountable recruitment and selection processes that ensure people working in the organization possess the knowledge, skills, and experience required to fulfill their roles. OECD recommends that public service organizations hire staff who reflect the diversity of communities served, creating a more efficient and empathetic public sector.