Executive Summary

The New York City Department of Veterans’ Services is one of the nation’s first municipal department level agencies dedicated to serving the needs of Veterans. Celebrating its decennial anniversary, the moment is apt for the Department to evaluate the past ten years, with an eye to the next ten. With more than 100,000 Veterans across the five boroughs, the needs of Veterans are unique and can prove challenging. Housing insecurity, mental health issues, digital access, continuing education, and financial insecurity are just some of the issues facing Veterans.

One of the smallest agencies in the city, DVS operates with less than one percent of the City budget devoted to it coupled with one of the smallest headcounts (less than 40 full-time staff). Maximizing resources is a challenge the agency faces as it works to deliver on its mission to: connect, mobilize, and empower New York City’s Veteran community in order to foster purpose-driven lives for US Military Service Members – past and present – in addition to their caregivers, survivors, and families.

The Department has tried to use its resources wisely, while recognizing that it cannot do it alone. DVS has created various support channels for Veterans to access its services and also collaborates with several government and non-profit agencies on a number of initiatives. These collaborations often result in what DVS calls “synergies”—indirect services made possible through working with external stakeholders. The combined effort of DVS and its partners leads to outcomes where the “whole is greater than the sum of the parts” or more substantial outcomes than either agency could achieve independently. In addition, the Department uses several strategies to increase awareness of the agency, such as using social media, newsletters, and engaging with community-based organizations. Further, DVS makes an effort to meet Veterans where they are likely to be. This is particularly true for the “invisible” Veterans.

It must also be recognized that there is a disconnect between the Department’s views of the success of its operations, and how Veterans, their families, and Veteran advocates view the Department. Through outreach with those same groups, there is a gap between the DVS’s reported practices and the experiences described by Veterans and advocates. The Department needs to rebuild trust with the New York City Veteran community. DVS needs to meaningfully and continually engage and the engagement must be integrated into DVS’ internal decision making.

The time has come for the Department of Veterans’ Services to strategically long-term plan for this next decade—what does DVS 2.0 look like? The partners are there, the vision must be too.

Key Findings

Recommendations prioritize communication, meaningful engagement, comprehensive case management, and long-term strategy planning.

- DVS makes an effort to meet Veterans where they are likely to be

- DVS has tried to use its resources wisely, while recognizing that it cannot do it alone

- There is a gap between the DVS’ reported practices and the experiences described by Veterans and advocates

- Continuity of care is critical to the long-term health, stability, and financial wellbeing of Veterans

- DVS has created various support channels for Veterans to access its services and also collaborates with several government and non-profit agencies on a number of initiatives

- DVS needs to rebuild trust with the New York City Veteran community

- DVS must do better in leveraging other NYC agencies to reach and serve more Veterans

As the Department of Veterans’ Services enters its adolescence, it should envision what a “DVS 2.0” should look like in this second decade. The partners are there, the vision must be too.

Leadership, Strategy and Direction

Service Delivery For New Yorkers

Relationships and Collaboration

Workforce Development

Financial and Resources Management

Digital

Government

Measurement, Analysis and Knowledge Management

Leadership, Strategy, and Direction

The Leadership, Strategy, and Direction pillar focuses on the capability of the agency’s leadership to properly steer the agency and prepare for the future. This review evaluates how the executive team and the agency as a whole develop, implement, and adhere to its mission, vision, values, and strategies.

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Leadership and Governance | C |

| Strategy Development | C |

| Strategy Implementation | C |

- Leadership and Governance

Agency Strategy

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an international organization that develops economic and social policy, identifies a “transparent and accessible” strategy as one of their principles of good governance. OECD lists various elements of how a “transparent and accessible” strategy can be accomplished; the first of which is making the strategy available online in an easily accessible format.

DVS has a variety of both short- and long-term strategies that center around the agency’s Charter-mandated focus areas: housing, healthcare, benefits, education, employment, and culture. Each strategy is tied to a specific program or initiative that advances the agency’s vision led by the Commissioner. Although many of the agency’s initiatives are listed on their website, none of their short- or long-term strategies are publicly available, making it difficult to understand what their overarching strategies are and what strategy each initiative is tied to.

Making the agency’s short- and long-term strategies publicly available on its website would help facilitate transparency and accountability. DVS’ staff emphasized to the assessment team that the Department is not a municipal equivalent to the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Instead, they said that DVS is designed to fill an access, service and benefit gap for New York City Veterans. DVS noted that the agency does not view its staff as caseworkers, with specific caseloads and client portfolios. Feedback gathered from stakeholders throughout this assessment period accentuates the need for a clear strategy that is publicly accessible. Advocates have noted that while DVS may advertise many offerings to Veterans and their family members, the substance behind these offers can vary considerably. Stakeholders mentioned that while DVS has taken on new initiatives, these can come at a detriment to DVS’ existing offerings and advocates shared that it is unclear what DVS envisions itself to be. Given that DVS was the first stand-alone municipal department dedicated to serving Veterans in the nation, and is approaching the ten year anniversary of its codification, DVS should lay out a clear roadmap of both short-term and long-term strategies.

OECD’s framework also asserts that for an organization to best support its strategies, roles responsible for implementation, monitoring, and evaluation should be clearly defined. Reviewing DVS’ job descriptions can identify how these responsibilities are delegated. Several DVS leadership positions were identified in this review:

- The Chief of Staff guides and supports “the design, implementation, and oversight for DVS’ current major programs and new initiatives.”

- The Senior Advisor of Intergovernmental Affairs provides “planning, coordinating and implementing interagency and agency-specific projects.”

- The Senior Advisor of Operations/Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) Officer “determine[s] and evaluate[s] the need for audits” and “oversee[s] the development and implementation of audit plans.” In addition, they “develop, implement, and monitor day-to-day operational systems and processes that support the unit and the agency’s key initiatives.”

- Both the Human Resources Manager and Generalist support the implementation of DVS’ Performance Evaluation Development Plan.

While these job descriptions highlight how DVS has established implementation, monitoring, and evaluation mechanisms and processes, these descriptions are not currently publicly available. Best practices also recommended that organizations establish clear descriptions of roles and responsibilities, including an organizational chart. Currently, job descriptions are only available if DVS has open recruitment on JobsNYC; however, DVS does outline its Executive Office and Senior Leadership team on its website.

- Strategy Development

Evidence-Based Practices

Ensuring that all stages of the policy development and implementation process and any strategic planning processes are based on the most reliable, relevant, independent, and up to date research should be a core practice of any governmental body. This ensures that the data gathered is based on the best practices in the field and that policy design and delivery are more successful, reflecting the needs and realities of the community.

When asked about the agency’s process for conducting strategic planning, DVS stated that their short- and long-term goals are shaped by community needs data, various agency feedback forums, and best practices. The agency also noted that they regularly use research from organizations such as the D’Aniello Institute for Veterans and Military Families, the VA, and the New York State Health Foundation to shape their strategic plans and reevaluate the agency’s strategic plans every quarter. However, some Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners feel that the results of the agency’s strategic plans do not necessarily reflect best practices or Veterans’ highest needs. When advocates and community-based organizations that work with DVS were asked if they felt the agency was transparent and forthcoming about their data, 62 percent of survey participants stated they disagreed, feeling that DVS was not transparent and forthcoming. Thirty-eight percent of participants also stated they felt the agency does not understand Veterans’ highest priority needs. Although DVS states it uses best practices and a variety of data to shape policies and plans, the negative sentiment indicated by the survey highlights a disconnect between how the agency develops and implements its strategic plans and how Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners feel it impacts Veterans. While DVS develops its strategic plans to the best of its ability, some improvements still need to be made in agency research practices as noted earlier.

Service Fragmentation and Overlap

When agencies have multiple programs that aim to achieve similar outcomes, it can result in fragmentation, overlap, or duplication of programming. Ensuring that any fragmentation, overlap, or duplication is intentional or planned helps eliminate inefficiencies, decrease costs, and can improve outcomes and impact.

DVS is one of the smallest City agencies and as a result, provides minimal direct services to Veterans. The services provided by the agency are as follows:

- Housing support services

- Housing preparation services

- Veteran status verification

- Vital documents collection

- Needs assessment

- Permanent housing placement services

- Aftercare services

- Rapid-rehousing assistance

- Eviction prevention assistance.

- Benefits navigation

- Assistance with filing VA Claims

- Support for indigent burials

- Support for enrolling in health insurance

- Client referrals

Due to the agency’s limited programming, there is no apparent overlap or duplication of programming. However, the agency’s inability to directly provide all necessary services has instead resulted in the fragmentation of its service programming. DVS refers Veterans to other city agencies, non-profit partners, and community-based organizations (CBOs) to fill resource and service gaps. This fragmentation was done deliberately because the agency lacks the necessary resources and/or staff to assist Veterans with all service needs. Due to the absence of overlap or duplication in programming, and the intentionality of its service fragmentation, the agency has shown exceptional performance and capability in this area.

- Housing support services

- Strategy Implementation

Improvement Mechanisms

Organizational performance is ultimately enhanced through continuous improvement. Improvement mechanisms should be integrated into all management and service delivery processes, as well as other necessary organizational processes, to maximize the outcomes for all stakeholders involved.

In response to a Council inquiry concerning strategies and mechanisms used to ensure continuous improvement, DVS responded that this area is discussed weekly at the agency’s team meeting. DVS noted that they have updated the agency’s weekly meeting agenda to include an “Issue, Discuss, and Solve” component where they review and evaluate program data and discuss how they can improve agency processes and service delivery. They also use quarterly emailed questionnaires to obtain feedback from the NYC Veteran community.

However, many advocates feel that while DVS may have improvement processes in place, it has not translated to consistent improvement of services, communication, or outreach. When Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners were surveyed about different aspects of DVS, such as service referral, communication, service design, responsiveness, etc., the overall response was negative. Almost half of the survey participants stated they felt that DVS does not operate in a way that supports innovation and diversity of service design and delivery models and 52 percent of participants felt that DVS employees struggle to demonstrate an understanding of Veteran and non-profit partner requests and communications.

The negative feedback from Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners suggests that the current improvement mechanisms in place need further refinement to ensure agency processes meet the needs of all clients.

Service Delivery For New Yorkers

The Service Delivery for New Yorkers pillar encompasses the accessibility, inclusivity, and availability of all agency services. This review measures how well the agency is accounting for and meeting the needs of the community using the resources available to the agency.

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Equity | B |

| Access | C |

| Meeting Demand | D |

- Equity

Information Accessibility and Outreach Efforts

Veterans are entitled to an array of benefits at the federal, state, and city level; however, many Veterans are often unaware of the support they have access to. Additionally, those that are aware of or are seeking out services may find benefit navigation difficult. To make navigating benefits a more equitable and accessible process, Local Law 113 of 2015 included a mandate that DVS inform Veterans and their family members of the availability of certain services, such as:

- Educational training and retraining services and facilities

- Veterans’ tuition awards

- Tutoring services

- Professional development and networking

- Health, medical, and rehabilitation services and facilities

- Federal, state, and city health plans

- Counseling services

- Provisions of federal, state, and local laws and regulations offering special privileges to Veterans and their families

- Veterans with Disabilities Employment Program

- G.I. Bill benefits

- Employment and re-employment services

- Free professional skills training

- Customized career-building tools

In addition to providing mandated information on the aforementioned services, the agency also provides resources on various housing services such as home energy assistance programs, New York City’s Housing Connect Program, and VA home loans.

Since DVS does not directly provide any of these services, they refer Veterans to CBOs, non-profit partners, or state and federal agencies that provide these programs at no cost. All City Charter-mandated service information is listed under the “Services” tab on the DVS website and links to external service providers. Veterans can also obtain more specialized assistance in understanding the availability of these services by requesting help through VetConnectNYC.

DVS aims to conduct outreach and make important information available through non-digital mechanisms; it is acknowledged that a subset of the target population will always be unwilling or unable to adapt to digital technologies, making non-digital mechanisms necessary to create a more participatory and inclusive public service design process. For example, a Pew Research Center survey found that although older generations, such as the Silent Generation, are using technology at higher and higher rates, they are much lower in comparison to younger generations, such as Millennials or Gen-Z. Of individuals between the ages of 74 and 91, 40 percent own a smartphone, 33 percent own a tablet computer, and 28 percent use social media, which makes it clear there is an overwhelming need for non-digital outreach.

When DVS was asked what forms of outreach they do to engage Veterans who do not have digital access or prefer non-digital mechanisms, they responded stating they use a variation of strategies to achieve this. The agency regularly engages with community boards, attending meetings and distributing materials to community board offices to hand out to constituents. DVS also tables at hospitals and various community events throughout all five boroughs where they provide Veteran resource materials, offer assistance with claims and other benefits, and answer any questions Veterans and their families might have. Additionally, the agency holds its own quarterly community engagement meetings with Veteran service organizations and CBOs to provide resources and spend time engaging with the Veteran community. For example, in August 2024, DVS held a community engagement session with Brooklyn’s Community Board 14 which focused on burial benefits, end-of-life benefits, the Final Honors Program, and more. Finally, DVS runs several programs, such as Veterans on Campus and Mission: VetCheck, and various events, like the annual Veterans Summit, that focus on outreach through non-digital means.

The agency measures both its digital and non-digital outreach efforts in the Mayor’s Management Report (MMR). The performance indicators used by DVS include online site visits, social media impressions, average newsletter subscribers, and public engagement events attended by DVS. While the agency appears to prioritize its digital outreach and impact, DVS has stated that the single indicator focused on non-digital outreach encompasses all of the agency’s efforts in this area. Although it might behoove the agency to create more specific non-digital outreach indicators to increase transparency, its performance continues to trend upward in almost every area.

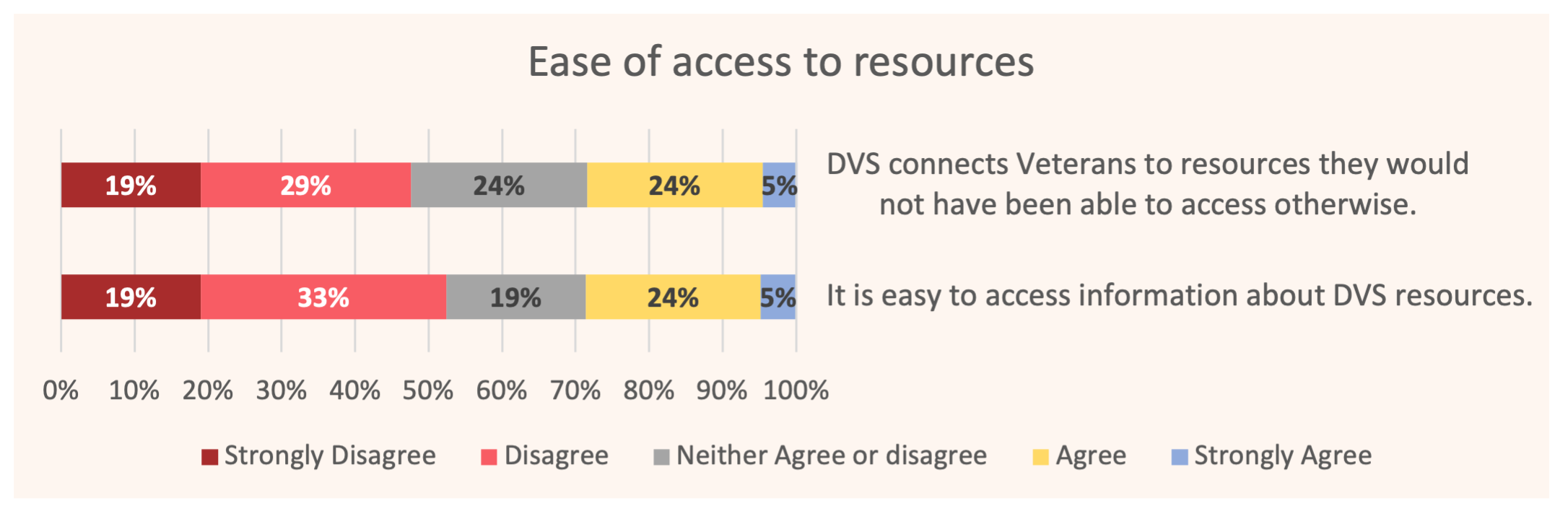

Despite the agency’s best efforts to provide easily accessible benefits information and non-digital outreach, it appears they may not be reaching as many Veterans as intended. In its 2021 Veteran and Military Community Survey, 4 in 10 Veterans were aware of DVS, with 58 percent of respondents not aware of DVS. When Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners were surveyed by the Council about the accessibility of information on DVS resources, 52 percent of survey participants responded they found it difficult to access the necessary information. One advocate stated that older Veterans who do not have computer skills have a harder time accessing information about the agency and their services. Given that 53 percent of New York City’s Veteran population is over the age of 64, a cause for concern is warranted. More than half of participants also felt that DVS was not conducting the necessary outreach to reach the largest number of Veterans, and 90 percent of survey participants remarked they felt that DVS should perform more outreach or diversify its outreach efforts. These responses indicate that despite the availability of the information and agency outreach efforts, there is still a disconnect between how information is presented and Veterans’ ability to access and understand it.

Services and Resource Inclusivity

Inclusivity is a key aspect of people-centric services: meaning that for an organization to ensure all services and programming are people-centered, they must be accessible to all segments of the targeted population.One aspect of ensuring total inclusivity is guaranteeing that agency programming offers operating hours that accommodate both standard and non-standard work schedules.

DVS has little to no in-person programming due to its limited budget and small staff. Despite limited staff and resources, DVS still funds and operates eight Veteran Resource Centers across all boroughs where Veterans can go and receive help from a care coordinator getting connected to services.Currently, the VRCs are only open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. two days during the workweek and are closed on weeknights and weekends.Although the days each VRC is open vary depending on the VRC, those days are fixed, lessening the flexibility of the resource centers.

When Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners were surveyed about the accessibility of the VRC operating hours, 43 percent of participants replied that they felt the VRCs were open at inaccessible times for working Veterans. One respondent commented that even when the VRCs are open, many Veterans have gone in and there is not a care coordinator present to help them.According to data from the 2021 DVS Veteran and Military Community Survey, almost half of Veterans in New York City work full-time, meaning that current VRC operating hours are inconvenient or inaccessible for nearly half of the city’s identified Veteran population.

In addition to ensuring inclusivity in services and programming, organizations must also ensure inclusivity in resources and information shared with clients to reduce barriers to accessing it. To achieve this, organizations should use plain language that everyone in the target population can easily understand.

The NYC Digital Blueprint describes plain language as “communication your audience could understand the first time they read or hear it.” It recommends that any organizational text written in plain language be written at an eighth-grade reading level, using shorter sentences and simpler words.The use of plain language improves organizational accessibility, especially when trying to reach individuals who have a cognitive or intellectual disability or whose first language is not English.

“Plain language is not “dumbed down” writing—it’s a way of writing that makes text easier for all readers to understand.”

In response to a Council inquiry, the Department stated using plain language that is clear, accessible, and easily understood is essential for them when communicating with the Veteran community. When asked how this is accomplished, the agency responded that they do their best to tailor the Digital Blueprint plain language best practices to the Veteran space due to the diversity in Veterans’ backgrounds and experiences. They also limit their use of military jargon and ensure they are sensitive to potential traumas when addressing healthcare, mental health, or other triggering topics in agency communications.Below is one example of the agency’s use of plain language, taken from an email sent to Veterans regarding DVS’ Veterans Voice Project:

“Dear NYC Veteran,

We hope this email finds you well. We are reaching out because you have expressed interest in participating in our Veterans Voices Project during a call with one of our Mission: VetCheck volunteers. Participating in the Veterans Voices Project is a chance for you to share your journey, memories, and reflections. It’s a space for your voice to be heard and your story to be preserved. The process is simple and can be done virtually from the comfort of your own home.

In preparation for your session and to schedule a recording, please click on the button below to fill out the google form. Once you’ve booked your session, we’ll provide you with further details on how to join the virtual recording. If, for any reason, you would prefer to participate in-person, please reach out to us and we will do our best to accommodate.

As you prepare for your session, we’ve compiled a series of questions to help guide your conversation. These questions are designed to spark meaningful reflections, but feel free to share whatever aspects of your story feel most important to you. Remember, your story is yours to tell, and we are here to listen.”

Despite the agency’s efforts to use plain language communication, a portion of the Veteran population is still struggling to understand agency messaging. In a survey to Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners, participants were asked about the clarity and effectiveness of DVS communications. More than one-third of participants indicated they felt agency communications lacked clarity and effectiveness. While other factors, such as the medium and timeliness of communication, may contribute to this issue, the agency’s communication may need improvements to enhance accessibility for the entire Veteran population.

- Educational training and retraining services and facilities

- Access

Availability of Assistance

Veterans are entitled to an array of benefits such as tuition support, income assistance, specialized health insurance, and affordable housing but often need support to navigate the benefits process. To address Veteran housing insecurity and the lack of awareness about available resources, comprehensive and accessible support must be available to Veterans to find and successfully secure housing. In DVS’ 2021 Veteran and Military Community Survey, 55 percent of respondents said they were seeking access to new housing and 50 percent said they were seeking access to better housing.

Obtaining certain benefits, such as affordable housing, are essential to a Veteran’s well-being but can be difficult to find and confusing to navigate alone. Needs assessments for Veteran and military populations in the United States point to a lack of awareness about available resources as a major contributing factor to Veteran homelessness, while insights provided by Veterans’ services advocates identify homelessness as one of the major issues affecting New York City Veterans. The Department does produce and make available for download on its website, a Veterans Resource Guide that lists housing services that Veterans and their families can avail themselves of.

DVS offers support for several housing-related needs such as rapid re-housing, paying for permanent or supportive housing, securing housing for elderly Veterans, and assisting with obtaining various housing loans. When a Veteran comes to the agency in need of housing support, they are assigned a housing caseworker who works closely with the Veteran to meet their needs. The agency expressed they do their best to provide seamless care coordination to Veterans in need of assistance, aiming to return client calls the same day, schedule appointments within a week of the client’s initial contact, and refer clients to partner agencies or providers when necessary.

That said, accounts from advocates and New York City Veterans at the Council’s roundtable regarding their experiences with DVS suggest that even though the agency provides housing assistance, Veterans continue to face difficulties reaching agency staff or experienced a lack of follow-through resulting in the Veteran remaining homeless and seeking housing assistance elsewhere. According to a member of the Veterans Advisory Board, communication is the biggest challenge with DVS and is a source of frustration for Veterans, advocates, and partners alike when attempting to work with the agency. An advocate from a legal services provider stated that they felt there was organizational chaos and a lack of responsiveness within the agency. When Veterans, advocates, and providers were surveyed about the efficacy of housing through DVS, only 24 percent of participants felt that DVS improved housing accessibility for Veterans while almost half of participants insisted otherwise. One advocate insinuated that DVS may not be best equipped to handle housing concerns stating that “they need to develop partnerships with other agencies that are better equipped to handle housing concerns.”

In addition to challenges navigating housing benefits, Veterans also struggle to navigate the claims process. A 2019 Systematic Review of Need Assessments on U.S. Veteran and Military-Connected Populations, by Ryan Van Slyke and Nicholas Armstrong of the D’Aniello Institute for Veterans and Military Families at Syracuse University, found that of 61 assessments on Veterans issues, Veterans across the United States noted a lack of education and information on VA and health resources available to them. The review also found that all the paperwork and bureaucracy required to apply for or submit benefits claims was extremely burdensome for Veterans.

To assist Veterans with these challenges, DVS does its best to provide claims assistance. Similar to the housing process, DVS assigns a state-accredited claims caseworker to each Veteran in need of claims support to help them through the process. DVS states that each caseworker conducts multiple follow-ups with clients to ensure their paperwork is filed and all issues are resolved as well as requesting that the client share any VA correspondence received, so the agency can assist in further issues. DVS also works to promote claims assistance for those who are unaware of the help the agency provides by supplying community boards with resource materials, attending community board meetings, and tabling at various hospitals and community events to offer claims assistance.

However, feedback from advocates and Veterans suggests that there is inconsistency in the level of training and aptitude to successfully submit claims on Veterans’ behalf and not enough personnel to fulfill the high volume of requests for claims assistance that DVS receives. It was even intoned that DVS currently has such a poor reputation for their claims assistance that “no one would refer to DVS for benefits,” partly due to an advocate’s belief that the agency’s claims assistance was being administered by non-accredited staff for a period of time. When Veterans, advocates, and providers were asked if the agency made claiming VA benefits easier and more successful, almost two-thirds of participants said no and only 20 percent of participants felt that the agency managed claims effectively and promptly. One advocated replied that the Veterans they have spoken with have not had any success submitting a claim with DVS while another advocate went so far as to say they would never refer a Veteran to DVS claims assistance.

Source: Department of Veterans’ Services Council advocate surveyAlthough DVS notes various ways in which they attempt to provide housing and claims assistance to Veterans, it is clear many Veterans are still struggling to get the support they need and communication lines between Veterans and the agency need imminent improvement.

Financial and Geographic Accessibility

Various factors, such as location and affordability, severely impact whether an organization’s services and programming are accessible to its target population. Ensuring services or programs are located within a reasonable geographic proximity and are provided at no-cost to clients enhances service accessibility, reduces economic inequality, and eases financial burden.

Veterans often experience challenges accessing resources due to geographic barriers. A review of prior Veterans needs assessment found that Veterans across the United States reported experiencing difficulties accessing VA and VHA health benefits and resources, often due to a lack of access to transportation. Since DVS provides minimal in-person programming and refers out to non-profit partners for a majority of needed services, the assessment team cannot evaluate the geographic accessibility of the agency’s programming. However, the agency operates eight Veteran Resource Centers throughout all five boroughs where Veterans can go to receive help obtaining benefits and get connected to essential services. VRCs “are satellite offices staffed by DVS Employees who are ready to connect Veterans and their families to benefits assistance and other essential services.” Due to Local Law 215 of 2018, which requires that there be at least one VRC in each borough, but a lack of funding to open more, there have been complaints that the current VRCs are tough to get to and located in areas with smaller Veteran populations. When Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners were surveyed about the VRCs’ accessibility, about half of the participants explained they felt the current VRCs are located in areas that are not easily accessible by public transit and are not hubs for Veterans. One survey respondent stated “We need to have a Bronx Veteran Resource Center in a better, accessible area in the Bronx, closer to public transit,” while another respondent said, “I’m a veteran living in eastern Queens and I’m not aware of any VRC near me.”

The agency’s 2021 Veteran and Military Community Survey shows that 41 percent of the New York City Veteran population receives VA disability compensation benefits suggesting the idea that almost half of the population may struggle to use public transit and could require alternate transportation to the VRCs. The agency itself has also noted that while having a space for Veterans to receive help in person is important, the current local law does not allow them to best serve the geographic areas with larger Veteran populations. While the local law mandates that there be a VRC in each borough, it does not specify where in the borough each VRC must be located giving DVS some agency over each location. Even though all of the VRCs are technically accessible by public transit, it does not mean they are accessible to all of the agency’s target population, and DVS should consider revising the VRC locations.

Since the agency has a limited budget to work with, only three care coordinators staff the VRCs, they are unable to open additional VRCs. The agency needs to improve the geographic accessibility of the VRCs, but it cannot do so without more funding for additional VRCs and a larger headcount.

Although the agency struggles with geographic accessibility, it excels at ensuring its services and resources are financially accessible. Any services provided by the agency are done so at no cost to clients and the agency ensures that any provider DVS refers Veterans to do not charge for their services. DVS states that “all organizations must provide free care to be offered as a resource on the agency website.” Additionally, the New York City Administrative Code requires that Veteran Resource Centers provide up-to-date information on housing; social services; applicable financial assistance and tax exemptions; discharge upgrade resources; and federal, state, and local benefits at no cost to Veterans.

- Meeting Demand

Referral Process

For an organization to meet the highest standard of service access, it must have processes in place to refer clients to alternative services if it cannot provide them with services due to ineligibility or lack of capacity. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs follows this protocol, having developed partnerships across the government and private sector to enhance its ability to deliver integrated care and services.

Due to DVS’ lack of direct service provision, it employs a strategy similar to the VA, providing Veterans with suggested providers they can connect with, as well as referring Veterans to non-profit or government partners for any needed services. They work with organizations that provide services to Veterans at no cost and refer them for services like legal support, financial assistance, employment resources, and healthcare services. DVS also affirmed that they ensure Veterans meet the eligibility criteria for whatever service and organization they are being referred to and help collect any necessary documentation for an outside organization to render services.

However, when Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners were surveyed about whether they felt that the referral services and organizations Veterans are being referred to are satisfactory—half of the survey participants disagreed. Thirty-eight percent of survey participants also responded that they felt the referrals made by DVS were not personalized and not facilitated well. Many Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners have also had issues with DVS’ VetConnectNYC portal, the main platform used to refer Veterans to services. Veterans needing services fill out an online form, which is then processed by DVS Care Coordinators who are supposed to contact Veterans in three to five business days. Unfortunately, when asked about the ease and usefulness of VetConnectNYC, almost two-thirds of survey participants responded stating that the system is not very useful and is not an effective or easy way to request services.

Although the agency has referral processes in place, it is clear that significant physical and digital infrastructure improvements are needed. It is not enough for the referral processes to exist if they are not effective and the community being served is not receiving needed care.

Care Continuity

Continuity of care can be understood as an individual receiving care at the same place from the same provider, or the seamless delivery of care through the sharing, coordination, and integration of information between different providers. While care provided at the same place from the same provider is optimal, it is recognized that a single provider is rarely able to meet all of an individuals’ health care needs. A 2015 Journal of the American Geriatrics Society research article found that veterans who have experienced higher continuity of care rates from the same provider are less likely than those who have experienced lower continuity of care rates to visit emergency departments (ED), be hospitalized, or have a history of depressive disorders. This cohort study in United States Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics in 15 regional health networks, ED, and inpatient facilities, resulted in the conclusion that:

“Even slightly lower primary care provider (PCP) continuity was associated with modestly greater ED use and inpatient hospitalization in older veterans. Additional efforts should be made to schedule older adults. with their assigned PCP whenever possible.”

Since older veterans tend to have higher rates of hospitalizations and are more frequent users of emergency department care, coordinated care may be even more important for this subset of the Veteran population. There is also evidence that continuity of care can improve veterans’ mortality rates, medication adherence, and the delivery of preventative care.

Given that 71 percent of New York City’s Veteran population is above the age of 55, ensuring continuity of care is especially important for DVS to effectively support the city’s Veteran population.

When asked about agency protocols for ensuring coordinated care for Veterans, DVS stated they work internally and externally to provide seamless care coordination. The agency uses a tracker to assign a caseworker to each client, provided the client does not need specialized housing help—in which case the client would be assigned two caseworkers: a claims caseworker and a housing caseworker. Once a Veteran receives assistance, the caseworker follows up at various intervals to understand the support’s success and identify additional assistance needed. At a meeting with Veterans Advisory Board leadership, it was mentioned that DVS has created a new database to improve their case management. If DVS cannot provide the necessary services, they work closely with partner agencies and non-profit providers, both at the city and state level, to refer Veterans for needed care.

However, the tone of Veterans, advocates, and providers regarding care continuity conflicts with the agency’s response. A variety of Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners were asked about their overall satisfaction with DVS’ care and only 10 percent marked that they felt DVS was the best care they had experienced. Almost 60 percent of respondents disagreed, replying that DVS was not the best care they had experienced, highlighting a discrepancy between sentiments within the Veterans community and the agency’s statement that they provide “seamless care coordination.” Survey participants were also asked whether DVS followed up to ensure referrals were successful, but only 15 percent of survey participants felt the agency did so while more than half of participants asserted that DVS did not follow up with Veterans to ensure successful referrals. Roundtable participants also noted that DVS lacks care continuity with the Veterans they serve, leading to frustration when a Veteran feels that they constantly have to start at step one as they work with DVS to resolve their issue.

Ensuring Communication and Support

An essential aspect of service accessibility and client prioritization is guaranteeing that agency support is available to all clients through various channels.DVS serves Veterans of varying ages, socioeconomic status, familial status, housing status, and locality—meaning that depending on a Veteran’s demographics, the method of support used will vary. Ensuring access to a wide range of support channels will allow DVS to better serve all Veterans.

After thoroughly reviewing the DVS website, agency support is accessible through the following avenues:

- Phone

- Requesting services on VetConnectNYC

- A “Message the Commissioner” form on the agency website

- Visiting a Veteran Resource Center

Though DVS has created multiple support channels for Veterans to use, many Veterans report having issues contacting the agency. When Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners were surveyed about DVS’ reachability, more than half of the participants responded that they did not find DVS employees to be very reachable or responsive to Veteran inquiries. Survey participants spoke specifically about calling the agency; they detailed getting anyone on the phone is difficult and many calls go unreturned. When asked about the VRCs, survey participants responded with a similarly negative sentiment stating that VRCs are open at inaccessible times for working Veterans and that staffing issues can lead to VRCs being closed at times when they should be open. An advocate commented on the VRCs saying, “Even though DVS lists when their VRCs are open, many veterans, including myself, have visited during those times with no one there.”

The City Council’s Oversight and Investigations Division (OID) completed visits to five VRCs in summer 2024, one in each borough, to gather information on location challenges, client volume, common services, and staffing challenges.

OID found that most of the resource centers were difficult to locate within the buildings where they are housed, due to a lack of signage directing clients to the office. The Bronx VRC even appeared closed during its allotted ‘open’ hours, as the lights were off and no staff were present. OID noted that each VRC only had one staff member on-site to assist with client concerns and all expressed the need for additional staff. The need for additional staff was emphasized by the Manhattan VRC being temporarily unable to assist walk-in visitors due to being short-staffed during OID’s visit. Lastly, staff estimated their average client visits at each site to be between two and four clients a day. While this could be because of a lack of client desire to visit the VRCs, it may be attributable to a lack of staffing or a difficulty in finding the resource center.

When asked about VetConnectNYC, Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners expressed frustration. Sixty percent of survey participants expressed that VetConnectNYC is an ineffective way to request DVS support or services and has not made requesting services easier. Since VetConnectNYC is generally the main way to request services from DVS, this poses a large barrier for Veterans in need of services.

Veterans and advocates have also struggled to reach DVS by phone, with some individuals stating the agency rarely answers the phone and seldom returns calls. “Communication with DVS is non-existent. They never answer the phone and when you leave a message, they never return the call,” said a frustrated survey participant. Another survey participant went so far as to note that they felt DVS has the poorest communication of any Veterans agency they have dealt with due to the difficulty of getting them on the phone. When DVS was asked about this in a meeting with the Council, they explained that they do their best to return calls the same day, but sometimes clients do not answer the phone causing a lag between the client’s initial call and when DVS is actually able to reach them. “We are calling back when it’s convenient for the team, but not necessarily convenient for the client,” the agency stated. They also mentioned that they will call clients back two and three times but sometimes run into the same issue of calling them at an inconvenient time. Lastly, they commented they have noticed that sometimes clients try to reach the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, not DVS, so they conflate the two agencies and find frustration with the wrong agency.

Although DVS has created various support channels for Veterans to access, it is clear there is still a major disconnect, and Veterans are struggling to obtain proper support from the agency.

In addition to ensuring continuous support, agencies must also ensure they are actively keeping all clients informed of changes to service or important updates through official agency sources, such as their website, newsletter, client portal, or email. Doing so enhances trust and transparency between the agency and its clients.

One of the agency’s main ways of keeping both Veterans and DVS partners updated is through their weekly newsletter. In a call with the Council, DVS shared that their newsletter has some of the highest engagement of all of their communication channels and typically has a 25 percent open rate. They also stated that they frequently share agency updates and important information at Community Board meetings and Veteran Advisory Board meetings, which can be attended both in person and virtually. Lastly, the agency will sometimes run print ads in local newspapers depending on the type of information they need to communicate with the public, such as the transition summits they have hosted with the Mets and the Yankees.

Unfortunately, despite the agency’s efforts to keep the public informed through official agency channels, some Veterans, advocates, and non-profit partners have expressed frustrations with the agency’s communication tactics. When DVS partners, advocates, and members of the Veteran community were surveyed about the effectiveness and clarity of DVS communications, more than one-third of participants indicated they felt agency communications lacked clarity and effectiveness. While other factors, such as the medium and timeliness of communication, may contribute to this issue, the agency’s communication may need improvements to enhance accessibility for the entire Veteran population. A few survey participants went as far as to say that they felt agency communications were nonexistent, while one respondent expressed that they felt communication was improving, but that the agency’s outreach was still poor.

This disconnect between the agency and Veterans shows that there is a portion of the target population that is most likely having to seek out information from the agency. Although the agency cannot ensure that all Veterans will see its communications, agency communication methods need improvement to ensure that Veterans do not have to continually seek out information.

Relationships and Collaboration

The Relationships and Collaboration pillar assesses how inclusive the agency’s policy design and improvement processes are. This review also evaluates how well the agency works with outside partners, since agencies often collaborate with outside stakeholders, such as community-based organizations and other governmental agencies, to achieve shared goals. The evaluation is conducted with an understanding that positive working relationships and collaboration are contingent on outside partners’ willingness to work with the agencies.

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder Engagement | C |

| Institutional Engagement | C |

- Stakeholder Engagement

Feedback Processes

The Human Services Quality Framework, created by the Queensland (Australia) Government, outlines how an accessible and effective feedback and complaint process is critical to an organization’s implementation of service delivery improvements.Under the framework, the Human Services Quality Standards (Standards) state that organizations should establish “fair, accessible and accountable feedback, complaints and appeals processes & client complaints” and demonstrate how these processes lead to service improvements. By collecting and incorporating feedback from Veterans, their families, caregivers, and active duty service members, DVS can ensure continued improvement in its operations.

Based on DVS’ responses to Council inquiries, the agency has an established process for resolving complaints. Senior leadership, overseeing the relevant topic area, follows up with the client who submitted a complaint within one to three days to “assess the situation and determine next steps. Complaints are then assigned to a staff member for resolution, and leadership follows up to confirm completion. However, a common theme observed in roundtables and surveys of Veterans and advocates has been that a lack of clear and consistent communication by the Department leads to constant frustration for Veterans and their families. While the Standards recommend that outcomes based on feedback and complaints be communicated to relevant stakeholders, most surveyed Veterans and advocates disagreed with the statement that “DVS manages client feedback and claims effectively and promptly” (29 percent strongly disagreed, 14 percent disagreed and 24 percent neither agreed or disagreed).

A key component of feedback and complaint processes is the availability of service-focused feedback or complaint forms for clients or family members. DVS reports that complaints can be submitted through their website, the ‘Contact the Mayor’ webpage, customer satisfaction questionnaires, or 311.” However, a review of DVS’ website found no service-focused feedback or complaint form currently available for Veterans, their families, advocates, or service providers to complete. DVS reports that most clients submit written feedback or complaints through the “Message the Commissioner” form, a freeform comment box.In addition, several unestablished methods are also used, including emailing the Commissioner directly, contacting through social media and LinkedIn, or speaking to their case manager or staff directly. DVS staff monitor the “Message the Commissioner” inbox during business hours to ensure no message is missed.

For clients engaged with services through VetConnect or other service streams, DVS sends quarterly customer satisfaction questionnaires throughout the referral process and when the client receives services. The Customer Satisfaction Survey focuses on gathering feedback about the experiences of Veterans and their families with the services or referrals provided. Quantitative and qualitative questions assess satisfaction in areas such as timeliness, staff knowledge, and the helpfulness of shared resources. The survey also invites open-ended feedback on service improvements and asks respondents whether they would recommend the services to others. DVS justifies this frequent solicitation of feedback because of how long it can take to receive benefits. While DVS’ services may end with a referral, the client receives services longer and may not immediately be connected to care.

It is critical for DVS to communicate feedback, complaints, and appeals processes to stakeholders so that the agency can understand gaps in service and the experience of Veterans, families, and service provider partners. The Standards recommend that human service organizations “efficiently communicate [these] processes to people using services and other relevant stakeholders.” Feedback from Veterans and advocates signals these processes are not communicated or advertised to those engaging with DVS: surveyed Veterans and advocates reported that “the agency does not ask for feedback.”

These responses further enforce the gap between the DVS’ reported practices and the experiences described by Veterans and advocates. While DVS outlines a structured feedback system, the feedback the Council has received indicates a gap between DVS and those outside DVS’ view of internal processes.

Participation

The OECD has established frameworks providing a public governance approach to policy that addresses unique and specific needs of vulnerable populations. The frameworks can assess programming and engagement with populations, such as Veterans, prioritizing “focused activities to promote participation and feedback from vulnerable and marginalized groups.” OECD further suggests that organizations “involve relevant stakeholders at all stages of the policy process, from the elaboration and implementation to monitoring and evaluation.” In this context, incorporating Veterans’ experiences can ensure that DVS includes their unique perspectives in policy and program development.

Such participation can be accomplished through “various tools and channels, such as face-to-face meetings, surveys, seminars and conferences, online consultations, and virtual meetings (webinars), radio, television, or print media.” DVS utilizes several of these methods, including the Veteran and Military Community Survey (the more recent of which was 2024) and public meetings. DVS noted several public forums where non-DVS affiliated Veterans can inform policy, including City Council Committee on Veterans oversight hearings, Veterans Advisory Board meetings, and DVS’ community engagement meetings.

However, there is a nationwide issue with Veterans not self-identifying. At an October 2024 oversight hearing held by the New York City Council Committee on Veterans, it was reported that approximately 35 percent of Veterans self-identify nationwide, with only roughly 24 percent self-identifying in New York City. The 2021 DVS Veteran and Military Community Survey found that 53 percent of Veterans feel lonely in a typical week and that Veterans “were more likely to seek help for physical ailments than other kinds of troubles, but even for physical ailments, about one-third of Veterans said they were unlikely to seek help.

Failing to reach those who do not initiate contact with DVS risks excluding a significant portion of Veterans from the policy process and service engagement. Each activity described above targets participation from Veterans who are already actively involved with or aware of the agency and services. To reach those not generally engaging with veteran services, DVS employs several methods to their messaging in non-veteran-specific spaces with a broad audience spectrum. Some examples include ads on iHeart Radio, community board meetings, and positioning staff in non-Veteran specific locations like Council Member offices. Being available at Council Member offices enables DVS to connect general constitutes to services and DVS.

Many Veterans fail to self-identify due to societal stigmas or personal reluctance. In Rand Corporation’s 2024 Needs Assessment Understanding Veterans in New York, researchers found the barriers to care differed from their 2010 Needs Assessment: “more [V]eterans in the current sample reporting not knowing how to find the proper services and believing that the care would not be effective.” While the focus of the needs assessment was on the United States Department of Veteran Affairs, broader research on engaging Veterans has found similar trends. Some Veterans “decide not to engage in community-based services due to strongly held views about receiving help for mental health issues,” viewing “asking for help … as a sign of weakness within the mindset of military culture.” The importance of engaging these unidentified Veterans has come up in recent testimony at City Council Committee on Veterans hearings, and DVS has acknowledged the need to connect these Veterans to services.

Awareness within the New York City Veteran Community

As a relatively new agency serving a vulnerable population, it is critical for the targeted population to be aware of DVS. The 2021 DVS Veteran and Military Community Survey revealed that about half of the overall surveyed participants (including Veterans, active service members, and family members) were not aware of the Department. Awareness and interaction with DVS were relatively low across the survey participants, with 30-36 percent aware and 12-18 percent having interacted with the Department. In response to this, DVS began several actions to increase awareness within the community. This ranged from quarterly written engagement with all CBOs, schools, VSOs, and other grassroots community organizations who have contact with Veterans, veteran resource guides, attending District Service Cabinet meetings for community boards in each borough monthly, and tabling at community events and partnering with existing community organizations, businesses, and schools. To gauge how aware the community is of DVS, the agency uses social media metrics, newsletter engagement, event registration, event turnout, and Community Surveys. The newsletter has been the most helpful tool for DVS, with a high open rate typically exceeding 25 percent. While event turnout is a useful metric, additional information is needed to understand who is in attendance. For example, at the 2024 Veteran and Military Family Summit at Yankee Stadium, 460 veteran community members attended. Of those, approximately 75 percent engaged with services, and 25 percent were personnel from various agencies or CBOs.

Despite these efforts, the ongoing challenge remains that many Veterans still need to gain knowledge of the full range of services DVS offers or the organization itself. Veteran advocates feel increased awareness within the Veteran community is still needed: of surveyed advocates in 2024, 48 percent felt Veterans are not aware of the full extent of DVS services. Further, Veteran advocates think many learn about DVS through VRCs or VetConnect, “the first touch to DVS is usually by word of mouth from another Veteran or from looking online.”

Source: Department of Veterans’ Services Council advocate surveyThe Engaging Veterans and Families to Enhance Service Delivery toolkit, created by the National Center on Family Homelessness, outlines best practices for effective outreach and engagement with Veterans, including both traditional outreach methods (e.g., direct, one-way communication such as flyers, print ads, and radio ads) and social media (e.g., either one or two-way communication via email newsletters, blogs, and social network sites). The Engaging Veterans toolkit acknowledges the challenges associated with Veterans who do not seek out community-based services, but blending social and traditional media has been found to help combat this.

Comparing recommended engagement tools with DVS’ reported practices confirms that DVS is using multiple of the best practices to engage with unidentified Veterans. DVS is employing several strategies to increase awareness of the agency, such as using social media, newsletters, and engaging with community-based organizations. Further, DVS makes an effort to meet Veterans where they are likely to be. This is particularly true for the “invisible” Veterans, such as women who do not self-identify as veterans. Moreover, the feedback from Veterans advocates signals that additional work is still needed. The downside of relying on social media and newsletter clicks with the Veteran population is that it is an aging population where a significant portion does not use social media.

- Institutional Engagement

As the Human Services Quality Framework outlines, strategic agreements and partnerships are crucial in helping an agency work effectively with community networks, other organizations, and government agencies to achieve desired outcomes. While DVS provides a handful of direct services, the agency primarily provides referrals to and partners with outside organizations and other City agencies. DVS’ key partnerships include non-profit and governmental agencies focusing on housing, employment, entrepreneurship, outreach, education, and culture.

The partnerships with each organization are structured in several ways, some based on formal written agreements, while others are ongoing, informal working relationships. As the City Charter establishes, DVS is not generally a contracting agency; therefore, they more often collaborate with or refer clients to agencies. As a comparison, DVS has entered a formal contract with the New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG) and the Veterans Advocacy Project to provide legal services for Veterans seeking discharge upgrades. This flexibility allows DVS to respond to the individual needs of Veterans and their families. In addition to the contracted organizations, some examples of the most common organizations DVS reports referring to are The Viscardi Center for employment training and job placement, Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) grantees (e.g., S:US and Jericho Project), and Volunteers Legal Services for support with will and estate management.

DVS also outlined several working relationships with other city and state agencies to help expand services, including the Department for the Aging, the Department of Small Business Services, the Department of Social Services, the New York State Department of Veterans Services, and the New York State Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance, among others. However, as noted later in Staff Development, advocates and current residents share that there is room for improvement in its collaboration with city agencies at shelters dedicated to Veterans (e.g., Borden Avenue). While the Borden Avenue shelter is not under the direct oversight of DVS but rather under the umbrella of the Department of Homeless Services, it remains important to note that many Veterans and advocates feel DVS does not have a presence at the shelter and services could drastically improve. The Department, in response to many Veterans and advocates feeling that DVS does not have a presence at the Borden Avenue shelter, wanted to make clear that DVS housing staff have maintained a steady presence at the Borden Avenue Residence since 2016. Staff are on-site every Monday, Wednesday, and Thursday.

DVS also collaborates with several government and non-profit agencies on several initiatives. These collaborations often result in what DVS calls “synergies”—indirect services made possible through working with external stakeholders. The combined effort of DVS and its partners leads to outcomes where the “whole is greater than the sum of the parts” or more substantial outcomes than either agency could achieve independently. In this design, DVS signals an understanding of the importance of collaboration in expanding its reach and enhancing its service delivery through direct services and referrals to external partners.

Example Synergies:

- Mission: VetCheck – Partnership with New York Cares

A wellness call program where trained volunteers make supportive check-in calls to Veterans and provide information on available support or services from DVS. Through this program, volunteers called more than 16,000 veterans in the NYC area in 30 weeks of the FY24 session. - CoveredNYCVet – Partnership with Mayor’s Public Engagement Unit & NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene

A CoveredNYCVet Specialist (from the NYC Public Engagement Unit) provides one-on-one support to Veterans and their families, helping them determine their eligibility for – and, when applicable, enroll in – VA healthcare, Tricare (Tricare is specific to certain military and retired military communities), and the New York State of Health. This reduces barriers to healthcare and streamlines processes for Veterans. - Military Family Advocate (MFA) Program – Partnership with NYC Public Schools

NYC Public School principals identify a staff or faculty member who will serve as said school’s MFA. The MFA is trained to inform and assist their school’s Veteran and Military families, acting as an extension of DVS. The program was recently expanded to be citywide during the 2024-25 academic term. - Veterans on Campus – Partnerships with colleges and universities

Proactively work with student veteran coordinators to get students involved and informed and assist academic institutions in adopting best practices for student veterans. DVS strategically targeted campuses with the highest veteran population at the onset to develop strong relationships, and it has since branched into every university in New York City.

Feedback from Veterans advocates, however, suggests that there are areas where DVS could improve its partnership approach. Advocates have expressed concerns that DVS’ partnerships are sometimes used only when advantageous to the agency. Most surveyed veteran advocates (43 percent) strongly disagreed with the statement: “DVS is taking advantage of all possible partnerships.” One advocate noted they believe DVS “lack[s] partnerships with a lot of organizations in the city.” However, the results were more mixed when considering the increased capabilities of the agency. For “[p]artnering with DVS enables partners to reach and serve more Veterans,” 24 percent of surveyed advocates strongly disagreed, and 24 percent agreed. These insights suggest that while DVS has established numerous partnerships, there is room for improvement in communication and collaboration.

DVS’ standard processes for sharing necessary information include public meetings, such as Veterans Advisory Board meetings and community board meetings, print advertisements in local newspapers and newsletters, or direct communication with advocates. When DVS uses direct communication, it depends on the type of advocate or agency; for example, DVS has held roundtable discussions with specific advocate groups in the past, such as street vendors, mental health providers, and Hispanic advocates.

DVS could foster more transparent, ongoing communication with advocates and non-profit organizations to enhance its partnership. Expanding roundtable discussions that include a broader audience on a routine basis could strengthen collaborations with agencies and build relationships between partners. This would also give Veteran advocates a clearer picture of DVS’ work with its governmental and non-profit partners.

- Mission: VetCheck – Partnership with New York Cares

Workforce Development

The Workforce Development pillar focuses on the agency’s staff capacity, training, and development. This review measures how well the agency maintains its headcount, trains and develops its staff, and ensures that staff are reflective of the communities being served. This pillar is evaluated with an understanding that the agency maintains and develops staff using the resources available to the agency.

| Indicators covered by the targeted review | Rating |

|---|---|

| Staff Capacity | C |

| Staff Development | C |

- Staff Capacity

Staff capacity can indicate an agency’s ability to meet the needs of its community, particularly in human service organizations that serve vulnerable populations like Veterans. Ensuring that staffing levels are sufficient and proportionate to the community’s demonstrated need is essential for effective service delivery.

As of January 2025, DVS employs 38 full-time staff across its nine divisions as outlined earlier under Structure and Resources. The Veterans’ Support Services and Housing & Support Services (HSS) divisions serve as the primary interface with clients, and DVS reports it prioritizes its staffing levels in these divisions based on the support and services that clients require: “client and community is at the center of all agency decision-making because the agency’s overall goal is to maintain and improve upon service delivery.” The largest share of the current DVS workforce (as of January 2025, 39 percent) are in leadership positions. The remaining workforce comprises back-of-house/operational staff (27 percent) and service-delivery staff (33 percent). While DVS has reported that many staff assist with phone calls or have frequent face-time with clients, only roughly a third of staff (all of which fall into the Veterans’ Support Services and HSS divisions) have assisting clients as a part of their job description.

DVS allocates five employees to Veterans’ Support Services, including one Senior Specialist and four Veteran Specialists, who report to the Senior Executive Director of Veterans’ Support Services. The Veterans’ Support Services unit, which combines the Claims and Referrals teams, aims to provide a holistic approach to serving Veterans. By combining these functions, DVS reports it can respond to the multi-dimensional needs of clients: while the five staff members are accredited to process and assist VA claims, they can also provide referrals to other services (e.g., housing or mental health) as needed. Therefore, the workload for a Veteran Support Services Specialist varies across the different functions: in November 2024, on average, there were 12 new benefits navigation cases, 61 claims, and 26 non-housing or claim referrals to services. There were also 142 housing support requests per Veteran Specialist during this month. While sometimes a client will have both a Veteran Support Services Specialist and HSS caseworker due to the specialization of the teams, there are also circumstances where DVS assigns one case worker to a client.

DVS’ HSS division consists of one Senior Veteran Housing Coordinator and two Veteran Housing Coordinators (VHC) who report to the Senior Executive Director of Housing and Support Services. VHCs provide housing support to clients by managing the intake process, advocating for Veterans in securing housing, and providing support in eviction prevention and rehousing assistance. Touchpoints for these clients sometimes overlap with claims and referrals, so VHCs work closely with Support Services staff. The current caseload ratio is approximately 30-35 cases per VHC.

Currently, HSS and Veterans’ Support Services staff VRCs each week. Under Local Law 215 of 2018, VRCs must be open at least ten hours per week per borough. HSS staffs the Chapel Street HRA office in Brooklyn two days a week, while Veterans’ Support Services staffs VRCs two days a week at the Bronx VA Medical Center, Queens Borough Hall, and Staten Island Borough Hall. In addition, HSS staff have a daily presence at the Borden Avenue Veterans Residence (BAVR), a veteran-specific shelter under the Department of Homeless Services umbrella.

Staff functional changes are prompted by the need for additional work in a specific arena or due to other dynamics, such as staff leave, new programming, and process improvement or adjustments.DVS’ headcount has varied over the past few fiscal years, with the agency filling 77-89 percent of its budgeted positions. This is lower than the citywide totals over the same years. Between FY21 and FY24, the City filled 92-98 percent of all positions.DVS has faced fluctuations in staffing over the past few years, likely due to the pandemic: in FY21, 39 out of 44 positions were filled (89 percent). By FY23, it had dropped to 32 out of 41 budgeted positions (78 percent). Budgeted positions slightly decreased the following year (FY24), with 32 out of 37 positions filled.

FY Budgeted Actual % Filled FY21 44 39 89% FY22 44 34 77% FY23 41 32 78% FY24 37 35 95% FY25 39 34 87% DVS reported frequently collaborating with the Office of Management and Budget to assess agency capacity and ensure that needs are adequately met. Though DVS is a relatively small agency, and “it is difficult to quantify the ‘ideal’ number of employees;” it leverages strategic partnerships, such as those with the New York City Council and local Veteran Service Organizations, to increase services. Despite these efforts, there is a discrepancy between the agency’s staffing levels and the community’s needs. Forty-three percent of surveyed advocates strongly disagreed with the statement: “at its current budget and staff capacity, DVS can serve the entire community and match its level and type of need.” Similarly, 38 percent disagreed, indicating that many feel DVS is not sufficiently staffed to meet the full range of needs within the Veteran community. There is also an outside sentiment that direct service providers are “overworked, thrown into the fire and get burned out.” Further, based on conversations with the Department, they recognize a need for additional staff to meet growing demands and expand services, especially if DVS expands its services or opens additional VRCs across boroughs.

- Staff Development

Recruitment

Organizations should establish “transparent and accountable recruitment and selection processes that ensure people working in the organization possess the knowledge, skills, and experience required to fulfill their roles.” As a city agency, DVS follows the standard Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) hiring process. In its approval process, new positions go through the Executive Team, Human Resources, Fiscal, and the Office of Management and Budget. Applicants who meet the minimum standards are interviewed, and the best fit is hired. When hiring for front-facing positions, DVS looks for several attributes. For Veterans Support Specialists, DVS prioritizes prospective applicants with “experience with computers and customer relationship management software, and reasoning and writing skills. A background or degree in social work or public policy may be beneficial, but it is not necessary.” Meanwhile, for VHCs, DVS indicated, “mental Health [and] Substance credentialed job seekers are strongly preferred.” As DVS follows the standard recruitment policies of DCAS, this targeted review will not examine these practices. However, DVS can inform the makeup of its staff within the hiring process by who is selected for hire.

The OECD recommends that public service organizations hire staff who reflect the diversity of communities served, creating a more efficient and empathetic public sector. In the context of DVS, Veterans must be prioritized in the hiring process. A review of DVS job descriptions reveals that hiring Veterans is highly preferred, with seven of 31 positions indicating “veteran status is a plus,” including the Chief Information Officer, Network Engineer, Veteran Support Services Specialist, Senior Director of Veterans’ Support Service, Final Honors Coordinator, Chief of Staff, and Transition Services Manager. If not a Veteran, DVS prioritizes those with “experience working with Veterans and Veteran families.” For front-facing roles specifically, DVS prioritizes hiring Veteran Specialists “who have familiarity with or an interest in Veterans benefits [and] military cultural competency” and VHCs with “prior experience working with the homeless population, veterans, case management/social services.” However, this cannot always be accomplished.

A shortage of Veterans in its workforce has been highlighted as a significant concern within the community: a Veteran advocate indicated that “there are … not enough [V]eterans at the agency” in its current state and that “this is a major complaint in the community.”

Further, staff “who are not Veterans working at DVS have not shown much cultural competency on the military/veterans issues.” Although DVS prioritizes veterans in its hiring process, the emphasis is mainly on leadership and managerial positions, with only two job descriptions in direct service roles directly prioritizing hiring Veterans. While DVS may hire Veterans for these roles, this also signals a potential gap between the perception within the community that DVS lacks sufficient Veteran representation, as the available Veteran-focused positions are often not aligned with the day-to-day needs of Veterans receiving services. These responses further enforce the gap between the DVS’ reported practices and the experiences described by Veterans advocates.

Training and Development

In addition to recruitment practices, training and professional development can enhance the productivity and skillset of an organization’s workforce. The Human Services Quality Framework recommends organizations provide “people working in the organisation with induction, training and development opportunities relevant to their roles.” Staff who work in front-facing roles also require training to be qualified to work with at-risk populations, such as trauma-informed customer service, crisis intervention, and de-escalation training. DVS requires staff who provide claim assistance to complete state accreditation training from the New York State Department of Veterans Services before processing claims for benefits. A Veteran advocate indicated that in the past, DVS only had one staff member accredited to provide claim assistance, signaling their capability to provide this service may vary over time. DVS also reported providing trauma-informed customer service training, crisis intervention, and de-escalation training to staff in front-facing roles, ensuring they are prepared to work with at-risk populations effectively.