Published Jan. 25, 2024, 7:34 p.m. ET

By Joe Borelli

Mayor Eric Adams vetoed two bills last week, including the How Many Stops Act. AP

In the classic prison film “Papillon,” when inmate Henri Charrière refuses to tell guards who helped him smuggle coconuts into jail, the warden punishes him by cutting his rations in half and confining him to a lightless cell the size of broom closet for six months.

“Darkness does wonders for a bad memory,” the warden sneers.

This scene made for some great drama about the notorious French penal colony Devil’s Island.

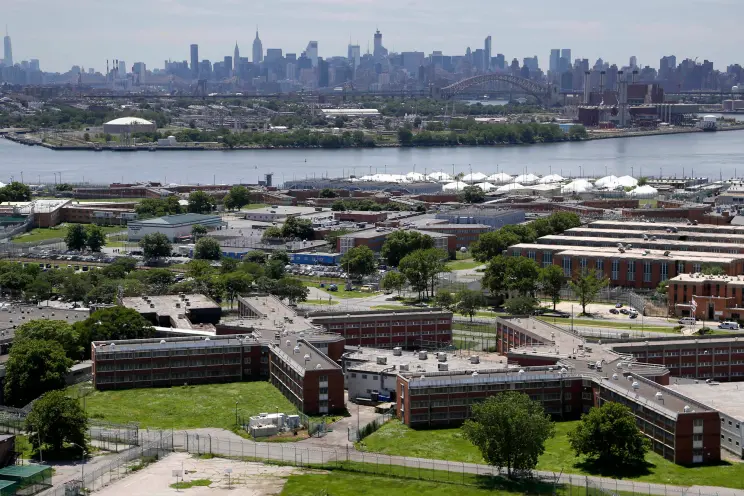

But “decarceration” activists would have you believe this same cruelty is a regular occurrence inside Rikers Island.

This inability to separate fact from film may explain why they’ve been cheering the December passage of a City Council bill that bans the supposed inhumane practice of “solitary confinement” in city jails.

The problem is there is no solitary confinement on Rikers.

The use of punitive segregation at the jail complex is nothing like “The Shawshank Redemption” or “The Hanoi Hilton.”

But it is the only tool the Department of Correction has left to quell the very real violence in the jail complex.

This legislation takes that tool away.

This was the second bill Mayor Adams vetoed last week, along with the How Many Stops Act, setting up a standoff with the City Council over where public safety in this city is heading.

It’s a scary direction.

Even Steve Martin, the federal monitor overseeing reforms at Rikers, sounded the alarm on this bill’s hazards.

In a letter to the council last week, Martin warned the “various operational requirements and constraints that accompany the elimination of solitary confinement in Council Bill 549-A will likely exacerbate the already dangerous conditions in the jails.”

What’s noteworthy is the federal monitor, who has been a scathing critic of just about everything the DOC has done since he was tapped in 2015, actually sides with the Adams administration on this issue.

All while wokesters on the left demand the federal government actually take over all the jail’s operations.

The reality is inmates placed in punitive segregation at Rikers are allowed social interactions, given time out of their cells each day for recreation and provided access to the library, health clinic and other necessary services.

While it’s not ideal to have to separate them from the general jail population, it is the hardly the torture depicted in the movies.

What else are correction officers to do to keep a violent inmate from attacking others?

That is exactly the question correction officers and others have posed.

The City Council’s response: Put them in “time out.”

If it were to become law, this legislation would only allow the DOC to separate a violent inmate from the general population to “de-escalate” for four hours during a 24-hour period, or 12 hours during any 7-day period.

To place an inmate in restrictive housing for any longer than that, the DOC would have to make its case in an administrative trial before the Board of Correction, and even then the segregation period could not exceed 60 days in 12 months.

Staff and mental-health professionals must also check in on the segregated inmates every 15 minutes, provide them with tablets or phones to make calls and fill out extensive reports justifying every action they take.

To be clear, I have punished my 8-year-old for four hours for far less, and he wasn’t afforded the privilege of his iPad.

DOC has taken punitive segregation off the table before, and the consequences have been disastrous.

In December 2014, then-Mayor Bill de Blasio stopped punitive segregation for 16- and 17-year-olds.

In 2016, the ban was extended to 18-year-old inmates and later to all inmates 21 and younger.

As a result, the rate of violent inmate-on-inmate assaults skyrocketed 68% between fiscal year 2014 and FY 2017, according to DOC data.

Even the Mayor’s Management Report had to admit the higher rates of violence were “a result of reducing and eventually eliminating punitive segregation.”

In fact, even after years of so-called criminal-justice “reforms,” violence at Rikers is more frequent and more brutal than ever.

In the 20 years between 1998 and 2017, as the number of inmates was nearly cut in half, the number of violent incidents doubled.

If the council wants to stem the tide of violence at Rikers, it can start by allowing the mayor’s veto of this legislation to stand.